“My Dear girl I hope again to see you. I must bid you farewell should I be killed. Remember if I die I die in a good cause. I wish we had a hundred thousand colored troops we would put an end to this war.”

- Lewis Henry Douglass, letter to Helen Amelia Loguen. July 20, 1863.

The story of Frederick Douglass is well known, but the story of his son, Lewis (1840-1908), is not. Frederick Douglass was one of the most important Americans of the nineteenth century. His autobiographies are both literary classics and invaluable historical sources. He published the first of these in 1845 when Lewis was five. At the time, they lived in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Frederick’s career as an abolitionist helped to pressure Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. In the Proclamation, Lincoln declared free any people enslaved in areas still controlled by the Confederacy. Lincoln also said, “that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States.” African Americans rushed to take up arms against the Confederacy.

Image: Lewis Douglass in Union Army Attire. New Bedford Whaling, National Park Service. (c1863-1865)

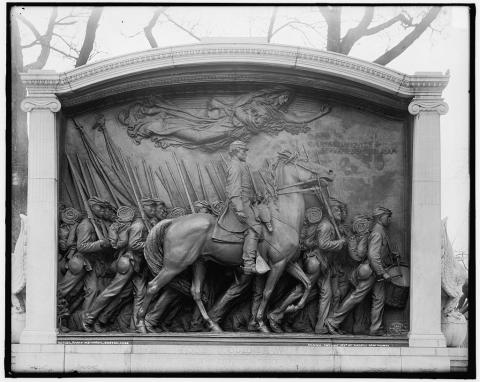

For the rest of war, Frederick Douglass worked tirelessly to recruit African American men to enlist to fight for the Union and to destroy slavery. Two of his sons, Lewis and Charles, volunteered to fight. On March 25, 1863 Lewis Henry Douglass, aged 23, joined the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the most famous African American unit of the war and the one immortalized in the film Glory. He was named the regiment’s sergeant major, the highest rank then permitted to an African American.

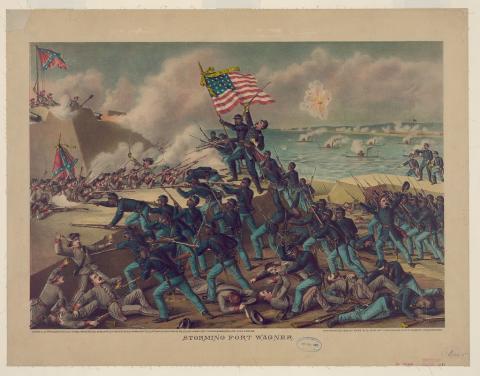

Lewis Douglass fought at the Battle of Fort Wagner, a decisive turning point in how white Northerners viewed Black soldiers and an event pictured in national media, including Harper’s Weekly. On July 18, 1863, Lewis wrote a letter to his future wife, Helen Amelia Loguen. He described a fight against a Confederate surprise attack. Though he was unhurt in that attack, he feared that he might be killed in the next. Yet he also recognized how crucial it was for African American men to help to defeat the Confederacy. He wrote, “My Dear girl I hope again to see you. I must bid you farewell should I be killed. Remember if I die I die in a good cause. I wish we had a hundred thousand colored troops we would put an end to this war.” That evening, his regiment led the attack on Fort Wagner. Half of the unit was killed or wounded, including its commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

The description of his injury is disturbing. He was examined in New York City on October 6, 1863 by Dr. James McCune Smith, the first African American to receive a medical degree. Smith wrote that Douglass “was very ill with diarrhea, cachexy [cachexia (muscle loss)] and spontaneous gangrene of left half of scrotum. He continues [to be] seriously ill at the present date… he is too feeble to be safely removed from this city and, in our judgment, several months must elapse before he will be able to do even the lightest military duty.” Lewis Douglass surely felt much pain and discomfort. Yet though disabled by the war, he did not apply for a disability pension.

Before the war, in Rochester, New York, Lewis Douglass had been a printer and typesetter, working to help produce his father’s newspapers, The North Star and Douglass’ Weekly. After the war, Douglass became the first African American to work as a typesetter at the Government Printing Office in Washington, D.C. He did not work there for long, though, because of the racially discriminatory policies of the typesetters’ union. For the rest of his life, Lewis Douglass remained active in Washington, D.C., politics.

Lewis Douglass finally received a disability pension on February 2, 1904 after suffering a severe stroke. He died in Washington, D.C., on September 19, 1908.

Sources:

- Case, John G. and Getchell, William Henry. (n.d.). Sergeant Major Lewis H. Douglass. Lewis Henry Douglass - New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Greene, R. E. (1990). Swamp Angels: A Biographical Sketch of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. BoMark/Greene Publishing Group.

- Storming Fort Wagner, Kurz & Allison. (1890). Library of Congress.

- Lewis Henry Douglass - Biographies - The Civil War in America | Exhibitions - Library of Congress. (2012, November 12). [Webpage].

- Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Sculptor. Shaw Memorial, Boston, Mass. Detroit Publishing Co., Publisher of photo. (1906). Library of Congress.

- Woodson, C. The Mind of the Negro. Lewis Henry Douglass letter to Helen Amelia Loguen. July 20, 1863. (Washington, D.C., 1926), 544. Library of Congress.