Cincinnati, Ohio. August 3, 1830.

(excerpted from The Works of Henry Clay Comprising His Life, Correspondence and Speeches.)

With respect to the American system, which demands your undivided approbation and in regard to which you are pleased to estimate much too highly my service, its great object is to secure the independence of our country, to augment its wealth, and to diffuse the comforts of civilization throughout society…

To the laboring classes it is invaluable, since it increases and multiplies the demands for their industry and gives them an option of employments. It adds power and strength to our Union by new ties of interest, blending and connecting together all its parts, and creating an interest with each in the prosperity of the whole. It secures to our own country, whose skill and enterprise, properly fostered and sustained, cannot be surpassed, those vast profits which are made in other countries by the operation of converting the raw material into manufactured articles.…

That system has had a wonderful success. It has more than realized all the hopes of its founders. It has completely falsified all the predictions of its opponents. It has increased the wealth, and power, and population of the nation. It has diminished the price of articles of consumption and has placed them within the reach of a far greater number of our people than could have found means to command them if they had been manufactured abroad instead of at home.…

That the effect of competition between the European and American manufacture has been to supply the American consumer with cheaper and better articles, since the adoption of the American System, notwithstanding the existence of causes which have obstructed its fair operation and retarded its full development, is incontestable. Both the freeman and the slave are now better and cheaper supplied than they were prior to the existence of that system…

We may form some idea of future abuses under the South Carolina doctrine by the application which is now proposed to be made of it. The American System is said to furnish an extraordinary case, justifying that state to nullify it. The power to regulate foreign commerce by a tariff, so adjusted as to foster our domestic manufactures, has been exercised from the commencement of our present Constitution down to the last session of Congress. I have been a member of the House of Representatives at three different periods, when the subject of the tariff was debated at great length, and on neither, according to my recollection, was the want of a constitutional power in Congress to enact it dwelt on as forming a serious and substantial objection to its passage. On the last occasion (I think it was) in which I participated in the debate, it was incidentally said to be against the spirit of the Constitution.

While the authority of the father of the Constitution is invoked to sanction, by a perversion of his meaning, principles of disunion and rebellion, it is rejected to sustain the controverted power, although his testimony in support of it has been clearly and explicitly rendered. This power, thus asserted, exercised, and maintained, in favor of which leading politicians in South Carolina have themselves voted, is alleged to furnish “an extraordinary case,” where the powers reserved to the states, under the Constitution, are usurped by the general government. If it be, there is scarcely a statute in our code which would not present a case equally extraordinary, justifying South Carolina or any other state to nullify it…

But nullification and disunion are not the only nor the most formidable means of assailing the tariff. Its opponents opened the campaign at the last session of Congress, and, with the most obliging frankness, have since publicly exposed their plan of operations. It is to divide and conquer; to attack and subdue the system in detail…

The American System of protection should be regarded as it is – an entire and comprehensive system made up of various items and aiming at the prosperity of the whole Union by protecting the interests of each part. Every part, therefore, has a direct interest in the protection which it enjoys of the articles which its agriculture produces or its manufactories fabricate, and also a collateral interest in the protection which other portions of the Union derive from their peculiar interests. Thus, the aggregate of the prosperity of all is constituted by the sums of the prosperity of each. …

The government of the United States at this juncture exhibits a most remarkable spectacle. It is that of a majority of the nation having put the powers of government into the hands of the minority. If anyone can doubt this, let him look back at the elements of the executive, at the presiding officers of the two houses, at the composition and the chairmen of the most important committees, who shape and direct the public business in Congress. Let him look, above all, at measures, the necessary consequences of such an anomalous state of things – internal improvements gone or going; the whole American System threatened, and the triumphant shouts of anticipated victory sounding in our ears – Georgia, extorting from the fears of an affrighted majority of Congress an Indian Bill, which may prostrate all the laws, treaties, and policy which have regulated our relations with the Indians from the commencement of our government; and politicians in South Carolina, at the same time, brandishing the torch of civil war and pronouncing unbounded eulogiums upon the President for the good he has done and the still greater good which they expect at his hands, and the sacrifice of the interests of the majority….

The blow aimed at internal improvements has fallen with unmerited severity upon the state of Kentucky. No state in the Union has ever shown more generous devotion to its preservation and to the support of its honor and its interest than she has. During the late war, her sons fought gallantly by the side of the President, on the glorious 8th of January, when he covered himself with unfading laurels. Wherever the war raged, they were to be found among the foremost in battle, freely bleeding in the service of their country. They have never threatened nor calculated the value of this happy Union. Their representatives in Congress have constantly and almost unanimously supported the power, cheerfully voting for large appropriations to works of internal improvements in other states. Not one cent of the common treasure has been expended on any public road in that state. They contributed to the elevation of the President, under a firm conviction, produced by his deliberate acts and his solemn assertions, that he was friendly to the power. Under such circumstances, have they not just and abundant cause of surprise, regret, and mortification at the late unexpected decision? …

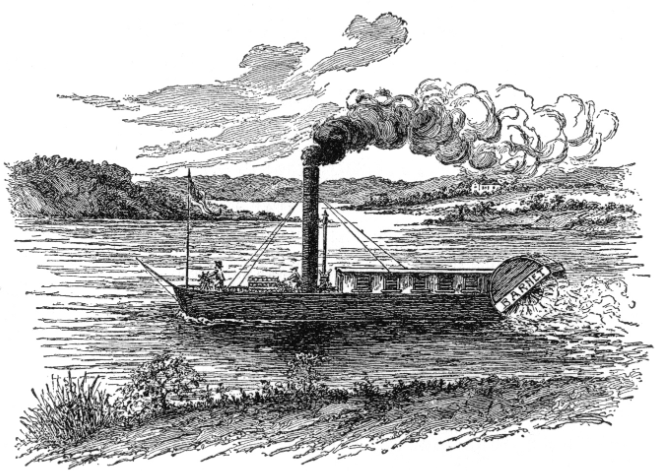

It is against the principles of civil liberty, against the tariff and internal improvements, to which the better part of my life has been devoted, that this implacable war is waged. My enemies flatter themselves that those systems may be overthrown by my destruction. Vain and impotent hope! My existence is not of the smallest consequence to their preservation. They will survive me. Long, long after I am gone, while the lofty hills encompass this fair city, the offspring of those measures shall remain; while the beautiful river that sweeps by its walls shall continue to bear upon its proud bosom the wonders which the immortal genius of Fulton, with the blessings of Providence, has given; while truth shall hold its sway among men, those systems will invigorate the industry and animate the hopes of the farmer, the mechanic, the manufacturer, and all other classes of our countrymen.

Source

The Works of Henry Clay Comprising His Life, Correspondence and Speeches, Calvin Colton, ed., New York, 1904, Vol. VII, pp. 396-415.