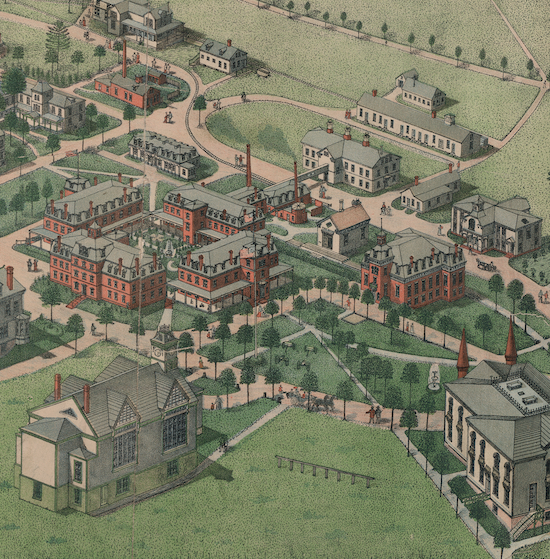

The first of the National Soldiers Homes was in Togus, Maine. In 1866, for $50,000 the federal government purchased a former resort at Togus Springs, four miles from Augusta, Maine. By 1870, the government had spent another $243,300 on improving the property. The number of disabled veterans living there rose rapidly during the years following Union victory. Within a year of its founding, 442 disabled veterans lived there. By 1878, 993 lived at Togus, and by 1904, at its peak, almost 2,800 men were cared for at the facility.

When Togus opened on October 6, 1866, and admitted its first resident, James P. Nickerson of the 19th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, its official name was the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. The word asylum signaled dependence and a lack of manliness by nineteenth-century expectations. To avoid stigma, in 1872, the name was changed to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Despite the change of name, the National Homes were not very homelike.

The various branches of the National Home, including Togus, and the largest in Dayton, Ohio, got much attention because of charges of abuse, immorality, and corruption. A Congressional investigation in 1884 stated that these institutions should be “homes for the country’s defenders, not asylums for the helpless poor.” Yet the report also found a depressing atmosphere of gloom. The managers of the National Home had to “deal with cripples, rheumatics, epileptics, dyspeptics, men who have been victims of excessive drink, depressed by a sense of advancing age and penury, men of all degrees of mental and moral development, who have no future to look to beyond the grave-yard in sight of the home.”

Nevertheless, there were many opportunities for paid employment. Togus maintained “a bakery, a butcher shop, a blacksmith shop, a brickyard, a boot and shoe factory, a carpentry shop, a fire station, a harness shop, a library, a sawmill, a soap works, a store, and an opera house theater.”

By all accounts, so did alcohol. All the National Homes were surrounded by places to buy alcohol, eager to take veterans’ pensions and earnings. Many veterans were willing customers. Some certainly became alcoholics. How much problem drinking was a direct result of trauma during the war is difficult to gauge, but is likely.

See also the story of Henry Meacham who lived at Togus.

Sources:

- Investigation of the Management of the National Home for Disabled Soldiers Volunteer Soldiers, by The Committee of Military Affairs, House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

- Kelly, Patrick J. Creating a National Home: Building the Veterans’ Welfare State, 1860-1900. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Marten, James. Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

- Eastern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Togus, Maine. Andrew B. Graham Co. lithographer. (1891). Library of Congress. One of the buildings on the grounds is a saloon.

- Togus, Maine; from an early twentieth-century postcard published by G. W. Morris of Portland. (1906). Wikimedia Commons.