Hundreds of thousands of disabled Union veterans sought financial assistance by applying to the Bureau of Pensions, a federal agency founded in 1832 but rapidly expanded after the Civil War. It eventually became a bureaucratic giant that managed the largest single item in the federal budget. The Bureau assessed disability claims and paid out benefits. In 1930, it was merged into the Veterans Administration.

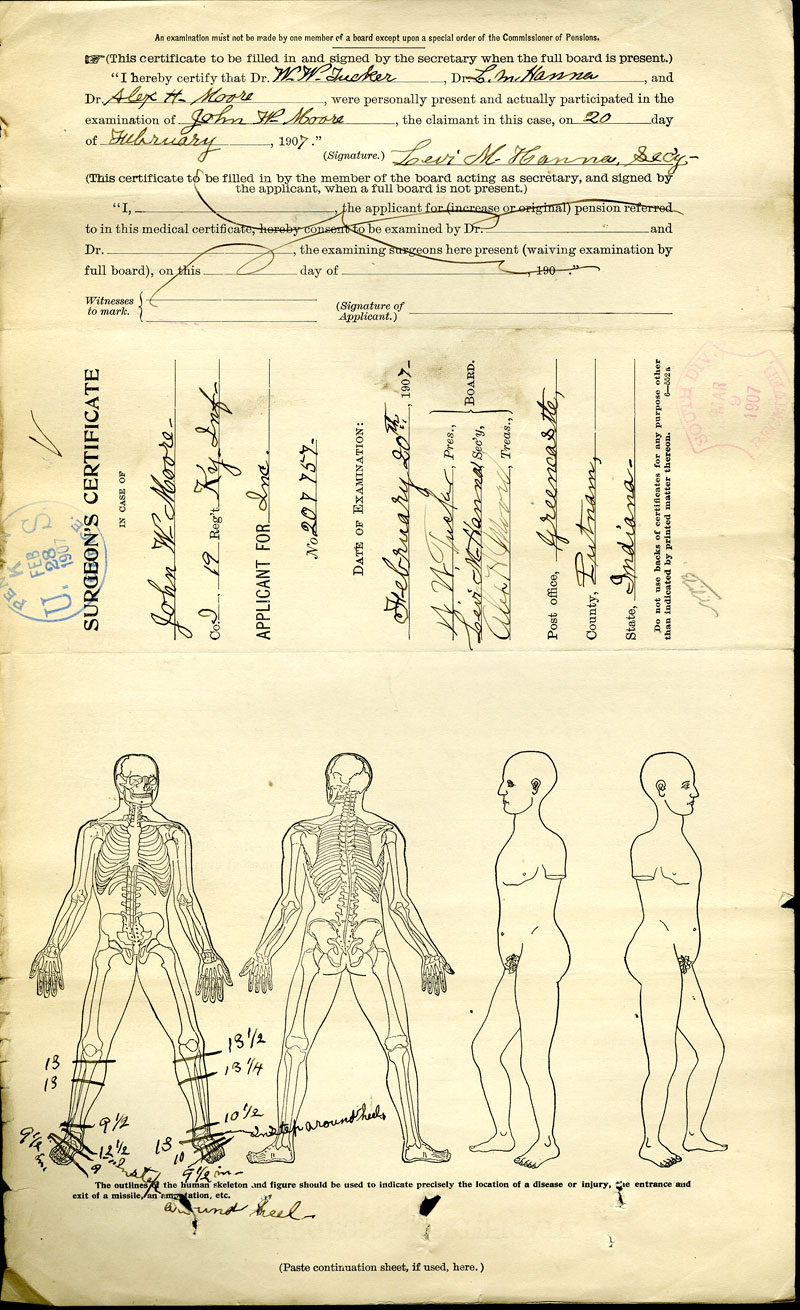

The first step in obtaining a disability pension was to get an examination from a physician. (During the war, physicians also provided certificates of exemption for draftees based on disability. The Civil War therefore represents a significant step in the medicalization of disability.) Medical examinations helped to determine how much money a disabled veteran would receive. The Pension Act of 1862 allotted $8 per month for an enlisted man who was deemed totally disabled. Officers received more. Over the years, benefits increased, and by 1907, old-age itself was considered a disability, and all Union veterans became eligible for pensions.

Civil War pensions also fostered the bureaucratization of disability. The pension process created huge amounts of paper records. So many that they proved deadly. Ford’s Theater in Washington became a clerk’s office for the Record and Pension Office of the War Department. On June 9, 1893, the building partially collapsed, killing 22 clerks and injuring 68. From 1887 on, the Bureau of Pensions was housed in an impressive edifice that today houses the National Building Museum.

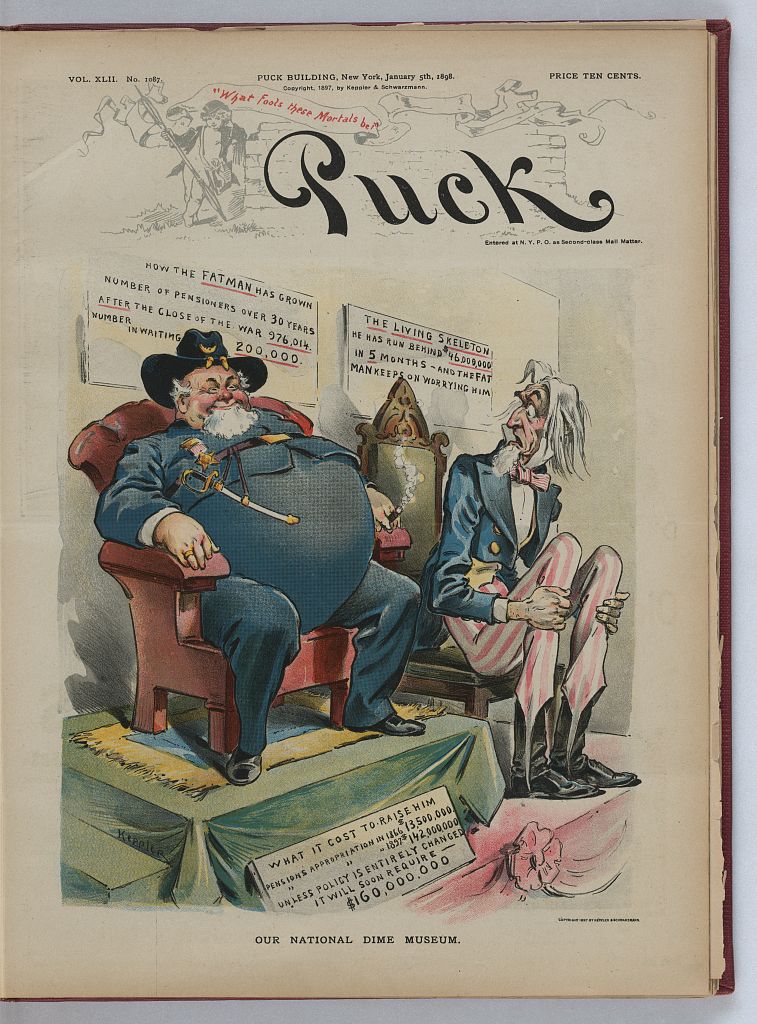

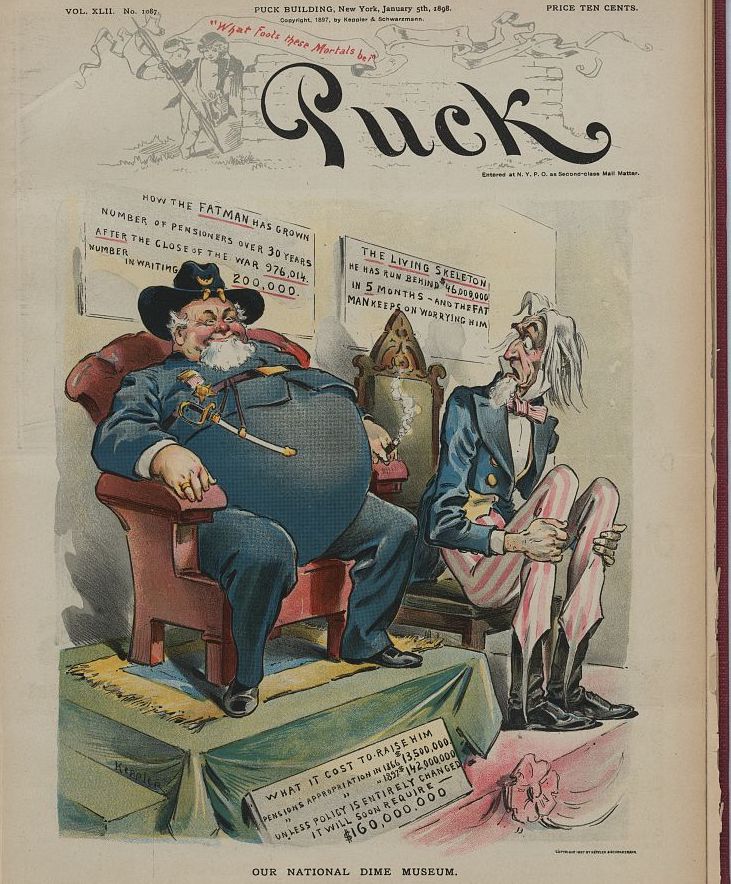

In the late nineteenth century, Civil War pensions and their costs became a major political issue dividing Republicans and Democrats. As pensions used larger and larger portions of the federal budget, resentments against such generosity sometimes turned to animosity against the veterans themselves. Opposition was popular with Democrats, who largely represented Southerners, and with recent immigrants, groups unlikely to receive Civil War pensions. The cartoon, “Our National Dime Museum,” from Puck magazine in 1898 portrays the Civil War pensions as the large veteran who consumes so much that he starves Uncle Sam.

Others avoided directly criticizing the veteran, but rather the “pension sharks” who took advantage of veterans who needed agents and lawyers to make their way through an increasingly bureaucratic world. Such opposition led American leaders to enact very different laws after the First World War. Policymakers during that war stressed vocational rehabilitation and employment instead of cash payments

Sources:

- Boynton, H.V. “Fraudulent Practices of Pension-Sharks; Uselessness of Pension-Attorneys.” Harper’s Weekly, March 5, 1898.

- Victor Gillam. “Throwing Light on the Subject.” (c1898). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015645585/.

- Logue, Larry M. “Union Veterans and Their Government: The Effects of Public Policies on Private Lives.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 22, no. 3 (Winter 1992). http://www.jstor.org/stable/204987.

- Prechtel-Kluskens, Claire. “‘A Reasonable Degree of Promptitude’: Civil War Pension Application Processing, 1861–1885.” Prologue Magazine 42, no. 1 (Spring 2010). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2010/spring/civilwarpens….

- Skocpol, Theda. Protecting Soldiers and Mothers : The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992.

- United States Pension Bureau, List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883 https://archive.org/details/listpensionerso03buregoog/mode/2up