The Connecticut River: Linking Trade Routes

Link to the primary sources discussed on this page.

The Connecticut River and its tributaries is a lifeline that connects the New England States of Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire. Beginning in the late 1600s the farmers who settled the fertile land in the Connecticut River Valley used the river for trade and transport.

Merchants and farmers relied on slow but sturdy flatboats to move their goods and farm produce up and down the river. Flatboats were rigged with sails to use wind power, but if the wind was down, a “poleman” propelled the boat using a long pole. Settlers used the river for trade and transport throughout the year, except in the spring when the ice broke up. In the winter when the river froze it served as an icy highway for sleds and wagons.

After the American Revolution, as the population grew the settlements along the river expanded. Trade increased and the river became an increasingly important link in a system of trade routes that eventually included the ports of distant lands, and river towns like Springfield, Northampton, and Hartford became bustling centers of commerce.

In 1794, an Act of Congress established the Springfield Armory to manufacture guns. Logging became an important industry, and logs were floated downriver from Vermont and New Hampshire. Flatboats transported the brandy and gin produced in Vermont distilleries. Shipyards grew, dotting the riverbanks. The river was rich in fish such as herring, shad, and cod. Merchants shipped the fish to the West Indies where it was essential in the diets of the slaves on the sugar plantations.

From Flatboat to Steamboat

The flatboats were slow to begin with, but rapids brought river traffic to a halt. The biggest obstacle on the upper river (the part of the river north of Hartford) was the South Hadley Falls. Workers had to unload flatboats below the falls and haul the goods above the falls with teams of oxen. This took a lot of time, and as the demand for trade goods increased, people wanted river transport that was more efficient.

Inventor

There were several advancements. In 1787, John Fitch, of Windsor, Connecticut, used a steam engine to power a vessel on the Delaware River. In 1792, Samuel Orford of New Hampshire developed a steamboat that traveled to Vermont towns on the Connecticut. Later he designed a sternwheeler that traveled upriver from New York to Hartford, but he lacked the capital to fund his inventions for commercial purposes. Until Robert Fulton popularized its commercial use in 1807 the steamboat was not widely used.

In 1792 business leaders from Northampton, Springfield, and Deerfield formed a group called “Proprietors of the Locks and Canals on the Connecticut River” to fund the construction of a lock and canal system. This would allow river traffic to bypass the South Hadley Falls. The canal system was a big success and trade jumped. Flatboats using the system carried iron, millstones, molasses, and rum upriver and agricultural produce, potash, lumber, and maple sugar downriver.

In 1813, the first commercial steamboat, the Juliana, sailed up the Connecticut River from Middletown to Hartford, Connecticut. Steam power cut the Juliana’s travel time dramatically, but flatboats continued to be the main mode of transportation on the upper river.

The American System

Two years after the Juliana’s first trip up the river, President James Madison proposed a plan to Congress to unify the country. His successor, James Monroe, supported it and the “American System,” as the plan became known, became an effort to unite the increasingly diverse economies of the North, South, and West in order to form a strong national economy.

Fifth President

of the United States

The American System established a national currency and funds for the development and improvement of infrastructure to facilitate trade. The North, South, and West disagreed about funding internal improvements—for example, the South relied on its river system and did not want to pay for roads built in the North and West — but New Englanders applauded the American System. They warmly welcomed President Monroe when he visited New England in 1817.

During Monroe’s presidency, a time dubbed the “Era of Good Feelings,” Americans built new turnpikes and bridges. New Yorkers funded the Erie Canal, which was completed in 1825 to connect the Midwest to New England and the Port of New York. River transportation was improved when Robert Fulton’s commercial steamboat began to carry freight and passengers much faster than the flatboat.

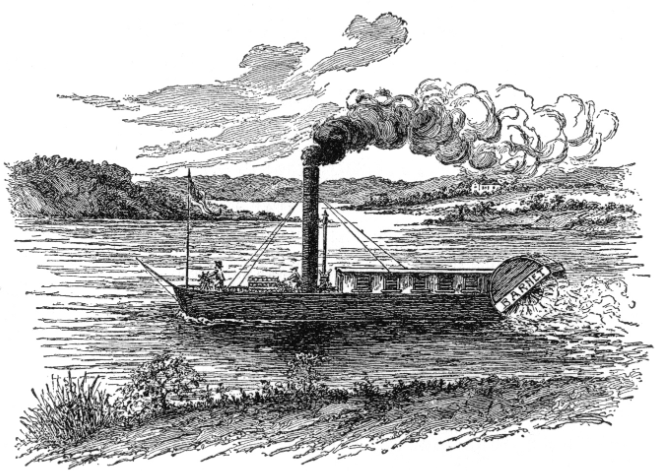

The Steamboat Barnet Emerges

However, instead of a strong national economy, three different economies developed. The North became a center of commerce and industry. The South became increasingly agricultural, producing mainly one crop (cotton) based on slave labor. The West, although it too was agricultural, relied heavily on new technologies such as the McCormick reaper and the steel plow to produce a variety of grains, foodstuffs, and livestock. Eventually, deepening cultural differences and the bitter divisions over slavery erupted into the Civil War.

Meanwhile, in the Connecticut River Valley, river commerce continued to grow. In 1822, William C. Redfield of Cromwell, Connecticut incorporated the Connecticut Steamboat Company, but company vessels navigated only the southern part of the river, below Hartford because of the Enfield rapids. Business leaders with plans for continued economic growth hoped that more powerful steamboats might someday get through them. That same year New Haven merchants, hoping to steal some of the river traffic from Hartford, obtained a charter to build a canal from New Haven to the Massachusetts border. In response to that threat, in 1824 the Connecticut River Company commissioned Brown and Bell of New York to build a boat that could successfully navigate the Enfield rapids. With that goal in mind, shipbuilders completed the steamboat Barnet in August of 1826.

In November, the Barnet set out from Hartford to Springfield, with Captain Roderick Palmer at the helm. At the Enfield rapids the Barnet struggled to make it through, but the rapids and a strong headwind forced Palmer to turn the boat back. On the next attempt the Barnet had a stronger engine and with the assistance of thirty polemen on flatboats the vessel passed through the rapids.

The Lathrop Letters

William Lathrop wrote letters to his father, Samuel Lathrop about the Barnet’s maiden voyage. His correspondence provides us with eyewitness accounts of the excitement surrounding the Barnet’s arrival in Springfield. People in the huge crowd that gathered to greet her knew that the Barnet’s arrival meant greater opportunity for them and commercial expansion for their city. The vessel’s first journey had proved that steamboat operations on the Connecticut River above Hartford were possible.

As local merchants had hoped, the Barnet’s success led to commercial growth in Springfield and Hartford. It also inspired other local entrepreneurs. Thomas Blanchard built a sidewheeler, and workers at the Springfield shipyard built the Vermont, which could pass through the canals at Bellows Falls.

The Barnet brought new prosperity to Springfield, but its success was short lived. In less than two decades the transportation revolution ushered in the railroads. In 1830 Massachusetts granted charters to railroad companies to develop rail lines out of Boston, and by 1844, a network of rail lines connected Springfield, Boston, New Haven, and Hartford. Railroads moved passengers and goods faster and more efficiently than steamboats.

For one brief moment in time, the Barnet captivated people in the Connecticut River Valley. The Barnet’s success contributed to the transformation of Springfield into a competitive commercial center that played an important role in the Industrial Revolution