Tewksbury was the last place a disabled Civil War veteran would want to be. For many residents, it was a place to die. Anne Sullivan, its most famous resident who would later become “Teacher” to Helen Keller, saw her little brother, Jimmie, die of tuberculosis there.

Many of the institutions and programs created and maintained at great public cost for Civil War veterans–state and federal soldiers’ homes, a generous pension system, and a Government Hospital for Insane Soldiers, for example–were created to keep veterans from ending up in almshouses. Life in almshouses was difficult and widely stigmatized. Soldiers’ homes and pensions were supposed to promote dignity and self-respect, while almshouses were the only choice for truly desperate people, especially people who were old or disabled, and penniless immigrants. Towns and states often spent as little as possible on almshouses, because they believed that otherwise there were many lazy people who would choose to live in them.

In the decades following the Civil War, social welfare policy followed two main tracks. One track was for veterans, supported by the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) and a Republican Party lobbied by the GAR. Governments generally funded that track well. The other track was for everyone else: immigrants, injured workers, children, and women. Most people saw those groups as worthy of private charity, but not public funds. Social Darwinism, and later eugenics, created the idea the poor were to blame for being poor. When “pluck and luck” failed, unlike the heroes in cheap, popular, “dime novels,” individuals would end up in places like the Tewksbury Almshouse.

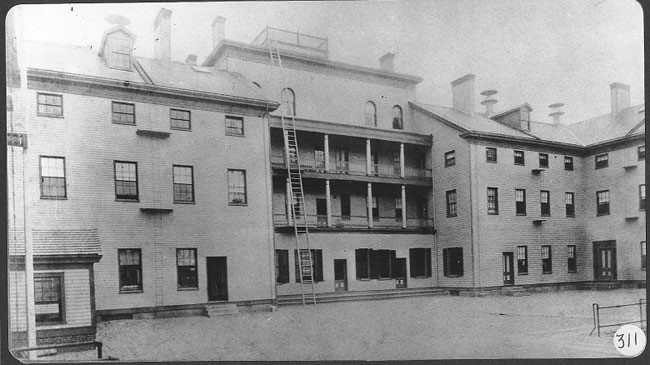

Opened in 1854 for “paupers” from Massachusetts, the facility quickly became crowded with immigrants, especially from Ireland. A third of the early inmates were children. Many of the residents were sick or disabled, and by the late 1880s, Tewksbury became a medical facility, treating poor people with physical or mental illnesses.

Anne Sullivan arrived at Tewksbury in February 1876 at the age of ten and would remain there until October 1880. Sullivan, whose trachoma infection badly damaged her eyes, was typical of people admitted to Tewksbury. From an Irish immigrant family, Sullivan lost her mother to death and her father to abandonment. In 1880, she was able to convince a powerful man, Franklin Sanborn, to help her go to the Perkins School for the Blind. The change that probably saved her life. She would later describe Tewksbury as “indecent, cruel, melancholy, gruesome.”

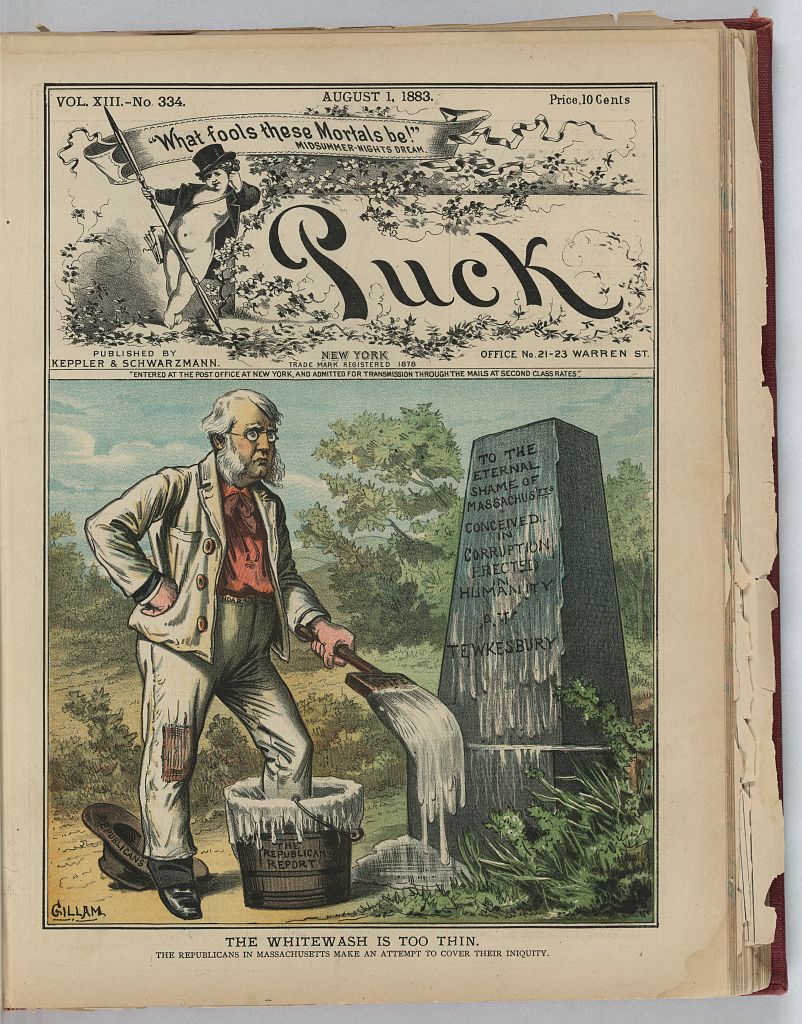

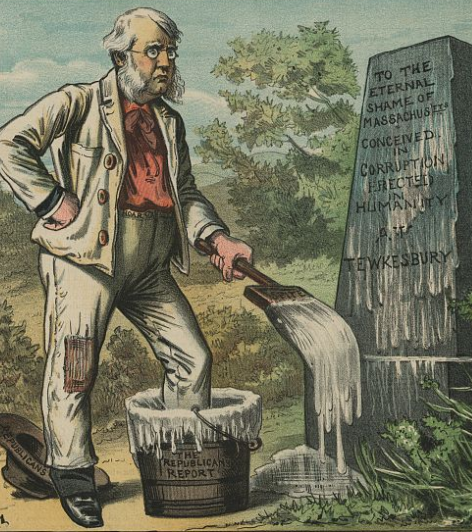

A public investigation of Tewksbury in the early 1880s supported Sullivan’s description. Led by Massachusetts Governor Benjamin Butler, the investigation accused the State Almshouse of corruption, abuse, and even the selling of corpses. It also revealed the terrible death rate of infants at Tewksbury. After these accusations became public, the head of Tewksbury was forced to resign. Republicans, the party then in power, who were more interested in funding pensions and soldiers’ homes, were charged with trying to cover up or “whitewash” the scandal.

Sources:

- “Anne Sullivan: The Miracle Worker,” American Foundation for the Blind. https://www.afb.org/about-afb/history/online-museums/anne-sullivan-mira… .

- Tewksbury Almshouse. Public Health Museum, Tewksbury, Massachusetts. (c1890). [Photograph.] American Foundation for the Blind.

- Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan. [1891]. Photograph by C.M. Bell. Library of Congress.

- Gillam, B. “The Whitewash Is Too Thin,” Puck. (August 1, 1883). Library of Congress.

- Skocpol, Theda. “America’s First Social Security System: The Expansion of Benefits for Civil War Veterans.” Political Science Quarterly 108, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 85–116.

- Wagner, David, Ordinary People: In and Out of Poverty in the Gilded Age (New York: Routledge, 2016).