“I have just got over that extreme soreness of the feet, which, I believe, has bothered all the nurses, except the real old stagers, whose muscles never surrender… The work is immensely hard, but I get used to it. If we could do it as citizens, instead of soldiers, it would be easy.”

- Hannah Stevenson, letter home, August 8, 1861

When Louisa May Alcott, the future author of Little Women, published her first book, Hospital Sketches in 1863, she dedicated the volume “to her friend Miss Hannah Stevenson” (1807-1887), the woman who persuaded Alcott to volunteer as a nurse. Stevenson was 53 years old and already a longtime abolitionist when she served as a Union nurse from 1861 to 1863.

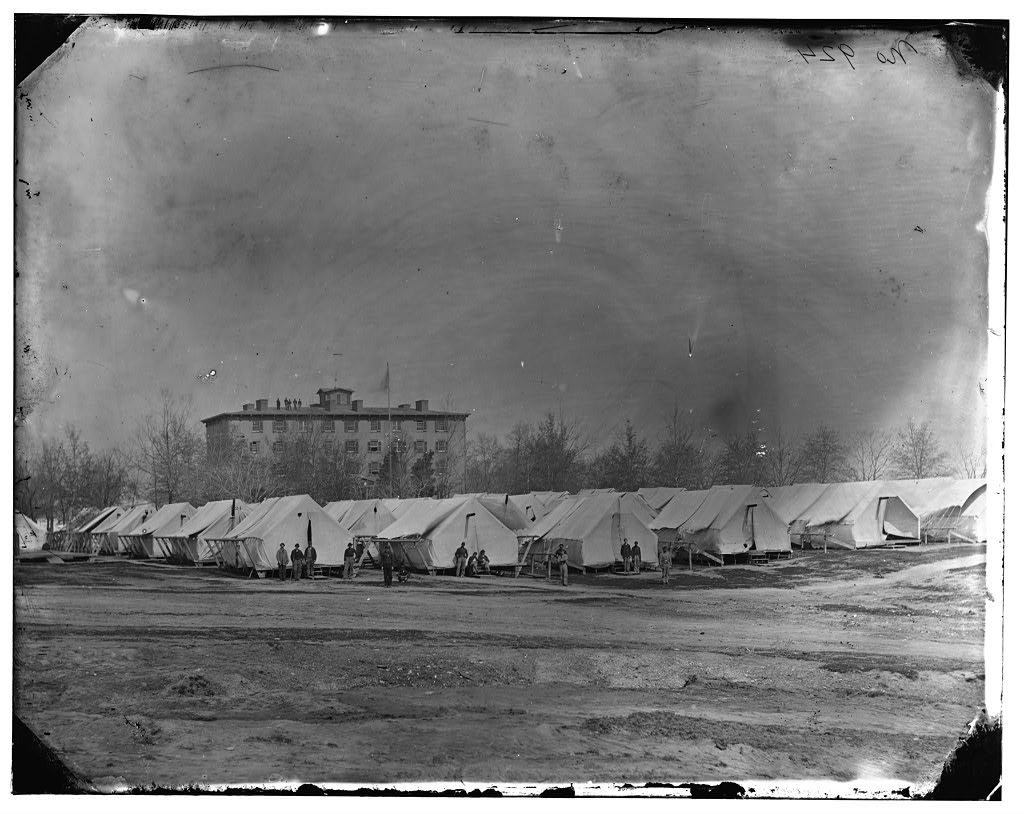

Stevenson had no formal training as a nurse. She had long worked at a home for poor children. Yet she became the first Massachusetts woman to volunteer. She worked at numerous hospitals, including Union Hospital in Washington, D.C., where she oversaw a ward receiving wounded soldiers from the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Like many nurses, Stevenson had a strained relationship with Army surgeons. Her letters complained about inefficiency and corruption, food shortages and medications that did soldiers more harm than good. In a letter dated August 8, 1861, Stevenson expressed dismay over how nurses were treated, “I cannot get over the surprise of being ordered about by these surgeons as they order the privates; they recognize nothing of the peculiarity of the position.”

Stevenson also noted how the war changed enlistees: “Strong men become babyish, youths without hope; cripples from rheumatism who never knew pain of body before; knapsacks lost with money, or all their clothes; homesick–oh! how homesick they are; how ignorantly careless of their health their commanders have been!” “Homesickness”or “nostalgia” was a name for a serious condition. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion, published in 1888, lists 5,213 official cases of nostalgia, including 58 that caused death. Soldiers could literally die of what was called homesickness. What might 21st century medical experts call these psychological illnesses?

After the war, Stevenson traveled to Richmond, Virginia, to help establish Freedmen’s Bureau Schools for formerly enslaved African Americans. She died on June 5, 1887.

For more information on nurses, see the article on U.S. Sanitary Commission.

Sources:

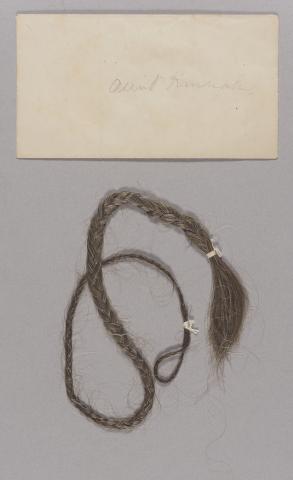

- Massachusetts Historical Society Collections: Lock of hair from Hannah Stevenson. (n.d.). In the 19th century, it was common to keep a lock of hair of a dear loved one. There is no known photograph of Hannah Stevenson.

- Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online: Letter from Hannah Stevenson to family and friends. (8 August 1861). Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- Washington, D.C. Hospital tents at Camp Carver, with Columbian College building. (c1862-1864). Unknown photographer. Library of Congress.

- Library of Congress screen cap from search result: “civil war nurse - Photos, Prints, Drawings.” Retrieved September 4, 2023. Pictured are E.M. Stone and several unidentified women.

- New York Historical Society. Nursing. Women & the American Story. Retrieved December 28, 2023.