“Believing that this principle and this law recognize no distinction of rights or rewards between the strong and the weak, the skilful and unskilful, the man and woman, the rich and the poor, asking only of all honest effort according to ability; that they never accord to property peculiar privileges, but seek only to bring mankind into harmony and union, to make the earth with its countless products the common equal heritage of the race as one great family, and to prepare this family by an enlightened and never-ending education to be peaceful, happy and active fellow laborers; never permitting strength to monopolize or skill to appropriate selfishly, but welcoming all to an equal participation of God’s blessed bounty.”

NAEI Constitution, 1842: Page 1 – Page 2

Experiment in Economics

So began the moral experiment and testing ground for overcoming the evils of the factory system and market economy. Throughout its short existence the members of the Northampton Association for Education and Industry attempted to create a new model for an existing society that they saw as wrought with immoral competition.

Industry in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

Image courtesy of Historic Northampton

The first half of the 19th century was filled with major economic change. The market revolution brought about a shift from self-sufficient local economic systems to a national and even international market economy. Improvements in transportation through canal systems and eventually railroads connected local economies.These connections facilitated westward expansion to the old Northwest for the establishment of cash cropping. Combined with development of the factory system, urbanization and the increased production of cotton, these changes created major upheavals in the social, political, cultural and economic lives of Americans. Northerners moved west. Farmers diversified. Sectionalism grew. Slavery expanded. Goods were made more readily available. Middle class family life changed as men left home to work and women remained as “guardians” of the home and its morals.

These changes brought new risks for many Americans. Small American farmers were challenged by the advanced technology and mass production of the cash cropping of the old Northwest. New England in particular suffered from failed farming and industry after the market revolution. The factory system created a wage-labor structure which was new for a primarily agricultural nation. Immigration from Ireland and Germany brought new culture to America—as the Irish worked in cities and Germans moved to the old Northwest. The growth of cotton production as a result of the cotton gin created a larger demand for slaves and changed the nature of the slave system. The growth of northern textiles factories established a direct affiliation with the cotton and slave system of the South.

Image courtesy of Historic Northampton

The risk, fear, and failure associated with the new market economy sparked resistance and reform. The Second Great Awakening began to push back on changes in faith which reformers associated with the materialism, competition and moral decay brought about by the effects of the Market Revolution. The Panic of 1837; alcoholism, poverty and crime in cities; decline in religious zeal; and increased materialism solidified the belief that society, especially its economic system, needed to be reformed.

The reforms of the 1830s and 1840s included a variety of topics including temperance, abolitionism, dietary reform, and others. These seemingly different issues all found some commonality in their attempt to find a new path for society based on expanded democracy and moral righteousness. Communal experiments became one such path for exploring a new model for society. Morally and economically attractive at the time, some Americans joined communities like Brook Farm, Oneida, New Harmony and the Northampton Association to seek reform for society.

Industry and the Northampton Association

The Northampton Association for Education and Industry was founded on the belief that they could pave that path for America. In the Association’s constitution the founders outlined an egalitarian enterprise that pushed the boundaries of social organization and capitalism and outlined a moral approach to work, wages and distribution of labor. The letters of Dolly and James Stetson outline a personal view of the association’s economic values, successes, and numerous failures.

The collection of Stetson letter were found with a small label-less wooden box filled with crumbling silkworms, old cocoons, raw silk and tiny brown paper packages tied with white silk thread (margorie’s article—put picture link here) The fact that these letters were found with the box of silk treasures is no coincidence. Although it became a major reason for the failure of the community, silk was a central factor in the lives of all members of the Association, especially the Stetsons’.

Despite initial reservations about its economic viability, the Stetsons decided to join the Association. For families like the Stetsons, the joint stock business plan offered an alternative to the economic problems many were facing throughout New England. Within their letters the economic problems at NAEI are clear from the beginning. To the Stetsons, these problems are real and affect their day-to-day life within the community.

James Stetson spends most of his time between 1843 and 1847 living outside of the Association attempting to sell silk for the community through known contacts and abolitionist networks. (18, 48) His time away from the community is the reason for the Stetson letters, as Dolly corresponded with him on a regular basis relating personal and community related news.

Day-to-day labor at the Association was divided among the members– men, women, and children all contributing. Although participation in the community was based on equality between all, there was a gendered division of labor based on rural New England society. All members were expected to voluntarily work as labor was seen as intrinsically beneficial and used as a method for reforming the body. The NAEI provided education for children that was based on a model of “learning by doing” and clearly stressed the role of hard work in developing values and work ethic.

This educational structure was also practical as children at NAEI became necessary actors in the economic survival of the community, as becomes clear in Almira Stetson’s grievances to her father. (35) Though some married women would have seen communal living as a loss of freedom, Dolly Stetson clearly benefited from the work-sharing model which gave her more time to read and expand her own education.

Their desire to stay true to an egalitarian model is clear through the many debates that show up in Dolly’s letters around wages, alternative production, child labor and work sharing. That NAEI included their economic system as part of their reform model, showed a more radical aspect than other communitarian reformers.

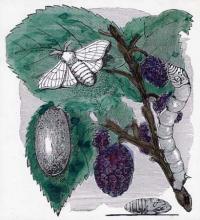

Northampton silk in the 1840s.

Image courtesy of Historic Northampton.

The decision to center the Association’s economic system on the production of silk was both practical and moral. Several of the founders were experienced in silk manufacturing and the property they purchased had been previously used for that purpose.

Silk also represented more to the community. As a free product, the production of silk did not rely on slave labor. From the beginning of the community, silk production could not produce the amount of money needed to sustain their community or pay back their initial debt. In addition, the process of cultivating silk and producing a salable product was difficult to say the least.

Collecting mulberry leaves, tending finicky worms, and unwinding the cocoons were all tedious, sometimes unpleasant tasks. Reeling consistently even thread required great skill and patience. (Watch a video demonstration of a silk reeler such as the one used at the NAEI.) Within less than a year, Dolly’s letters begin to discuss the troubles with silk production and its effect upon the community. In the 1840s, the silk industry was still young. Though others later found success with the production of silk products, they did so using already reeled silk from China and Japan.

Through its existence the Association discussed expanding into other plans such as Fourierism and products such as cotton. Because many of the members offered other skills the community was able to rely on mixed economic activities to offset lack of success with silk—lumber, carpentry, shoes, farm and garden produce, metalwork, machinery were all produced and practiced at the Association. The Association’s charge was to create a society worthy of God. Their industrial model needed to match.

Company’s Corticelli Silk, showing a

silk worm and listing the many

products of the mill.

When the community finally broke up in 1847, many of its members remained in Broughton’s Meadow (later renamed [permalink href=”1365″]Florence[/permalink] as a marketing tool), and continued to carry out the visions within the new neighborhood.The silk industry there eventually became hugely profitable. (Learn more at Smith College’s Northampton Silk Project site.)

Despite earnest attempts to reform, rework and restructure that model, the NAEI was unable to create a community that could sustain itself economically. Naïve planning, regional weather, lack of new technology and resources, and debt all contributed to the ultimate failure of the Association. As one of many failed business ventures of the 1840s, it should be no surprise that they were unsuccessful. Rather, the surprising thing is that they lasted as long as they did.