In the decades after the Civil War, there was no separate organization representing disabled Union veterans. Instead, like many other veterans, they joined the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). The GAR became very effective in pressure politics, especially in its promotion of veterans’ pensions in the late nineteenth century. It was, in effect, both a fraternal organization and a political advocacy group.

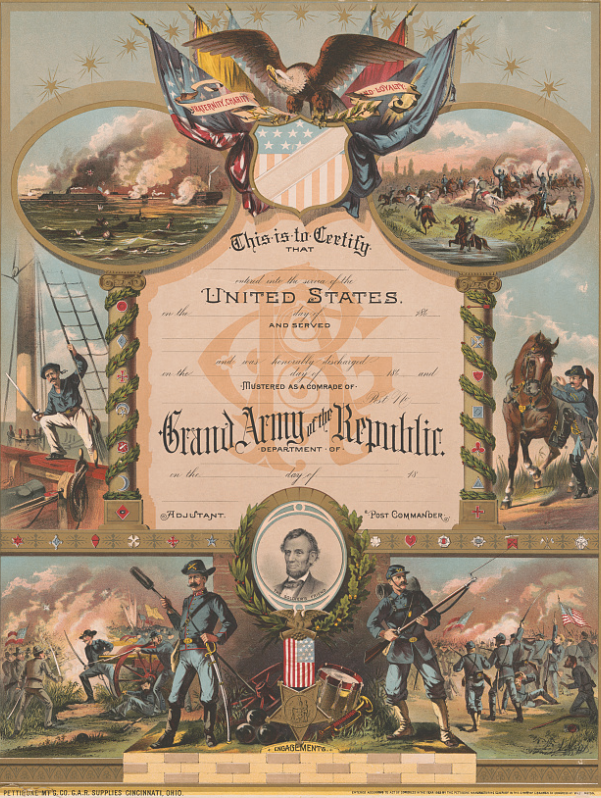

Fraternal organizations were popular in nineteenth-century America. These included Temperance societies, Freemasons, the Odd Fellows, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, and the Knights of Columbus. These gave men a place to socialize and to get support during a time of great changes in society. Under the slogan, “Fraternity, Charity, and Loyalty,” the GAR met similar needs for Union veterans.

Founded on April 6, 1866, by Major Benjamin F. Stephenson, a surgeon with the 124th Illinois Infantry, the GAR grew rapidly in the 1880s and reached its height in the 1890s, with 450,000 members and 7,500 Posts nationwide. It sought to recreate the comradeship of military service, and its organization mirrored military hierarchy, including a national “commander-in-chief.” Local posts modeled meetings and initiations on the rituals of Masonic lodges.

If GAR Posts provided opportunities for comradeship and shared memories at the local level, the national organization quickly became a powerful political force, especially within the Republican Party. They established soldiers’ homes, helped make Memorial Day a national holiday, and lobbied effectively for larger pensions for Union veterans. Five Presidents (Grant, Hayes, Garfield, Harrison, and McKinley) were GAR members.

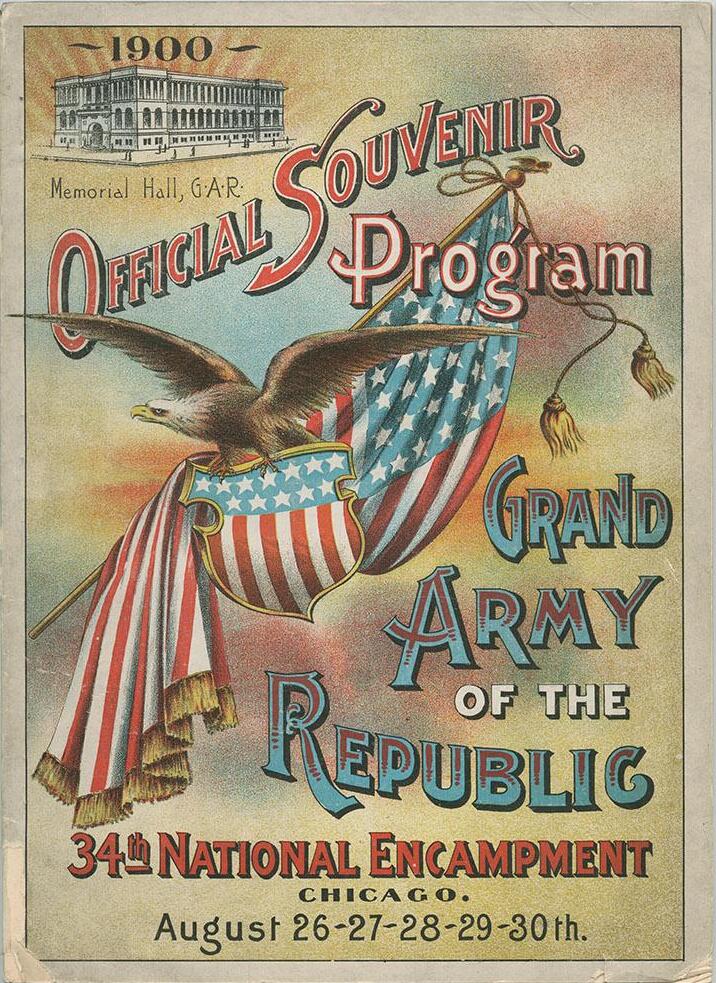

One of the biggest benefits of the GAR were many annual encampments. These gatherings lasted for days and included camping out, formal dinners, speeches, and ceremonies. The encampments brought economic benefits to host sites. They are an example of how memorializing the Civil War made money for some in the late nineteenth century.

The Grand Army of the Republic did help disabled veterans but often used amputees, or “living monuments,” as symbols leveraged to ensure more generous pensions for all Union veterans. The stress on amputation as the quintessential Civil War disability meant that those with less visible, and more common, disabilities received far less sympathy, attention, and assistance.

Sources:

- Grand Army of the Republic. National Encampment bulletin. (1900). Wikipedia.

- Grand Army of the Republic. Service certificate. (1884). Library of Congress.

- Jordan, Brian Matthew. Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War. New York: Liveright, 2015.

- McConnell, Stuart. Glorious Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865–1900. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Marten, James Alan. Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

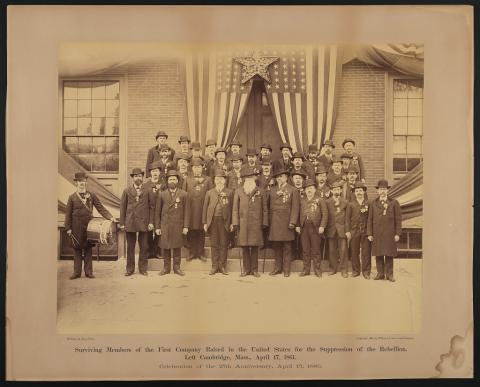

- Surviving Members of the First Company Raised in the United States for the Suppression of the Rebellion. Left Cambridge, Mass., April 17, 1861. Celebration of the 25th Anniversary, April 17, 1886 / Whitney & Son, Photo.

- Photograph by M.H. Reamy. Civil War veteran and amputee Henry A. Seaverns of G.A.R. George W. Perry Post no. 31, Scituate, Massachusetts, in uniform with sword, canteen, and other artifacts, standing on crutches in front of American flag. (c1893-1894). Library of Congress.