“The generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing.”

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Memorial Day speech, May 30, 1884.

The Civil War was deeply traumatic for Americans. Four years of war between 1861 and 1865 killed 750,000 Americans, destroyed the institution of slavery that had shaped the South, and changed the relationship between the citizen and the nation. For one man from an elite Massachusetts family, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1935), the Civil War was particularly traumatic. If the Civil War made America a different country, the war made Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., a different man.The physical and psychological impacts of his wartime experiences changed him forever. Ironically, despite his own disabilities from the war, his 20th century career as a U.S. Supreme Court Justice would profoundly harm people with disabilities.

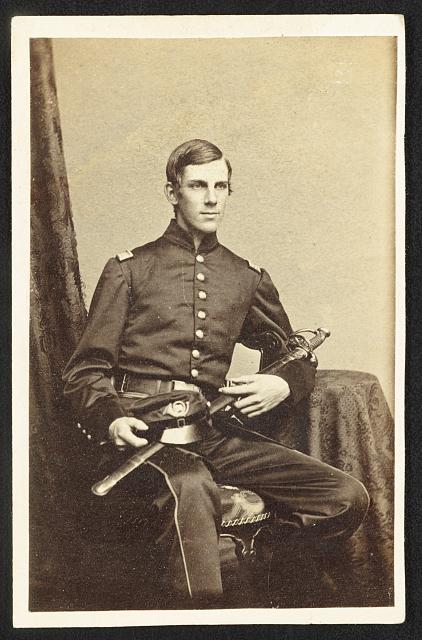

Image: Colonel Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (c1861-1865).

Holmes was the son of Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., the dean of Harvard Medical School, a poet, and a frequent contributor to The Atlantic Monthly magazine. In 1863, Dr. Holmes wrote that though American industrial technology was reaping “a melancholy harvest” of shattered bodies on the battlefield, American know-how would manufacture such wonderful artificial limbs that physical disability would be rendered meaningless. With such faith in progress, Dr. Holmes was an optimist. So was his son, or at least, he started that way.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., began the war as a hopeful abolitionist, committed to war as a liberating crusade. In the spring of 1861, Holmes joined the Union Army alongside his Harvard classmates, many of them close friends. His early moral commitment was sorely tested by the suffering he witnessed and experienced.

At Harvard, Holmes’s abolitionism made him something of a student radical. When Confederates fired the first shots at Fort Sumter in April 1861, Holmes quickly accepted a commission as a lieutenant in the Twentieth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the so-called “Harvard Regiment.” Over the next few years, he endured three grievous wounds that easily could have killed him. In 1861, he was shot in the chest at Ball’s Bluff, an early Union disaster. In 1862, he was shot in the neck at Antietam, the single bloodiest day in American military history. And in 1864, as Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee were slugging it out in Virginia, Holmes was shot in the foot at Chancellorsville. By then, Holmes was so disenchanted by the chaos and incompetence of the war that he hoped his foot would be amputated so that he could leave the army.

According to historian Louis Menand, though, “Holmes recovered from the wounds. The effects of the mental ordeal were permanent.” For Menand, the war made Holmes, “lose his belief in beliefs.” After the war, Holmes looked cynically upon a grimmer, less hopeful world. It is hard to say whether Holmes experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), because the diagnosis did not exist in the Civil War era. Medical authorities used very different language to describe the psychological disorders the war produced. It is clear, though, that the Civil War was the defining experience for Holmes. For the rest of life, despite his many other achievements, Holmes identified himself first as a Civil War veteran.

At a gathering of the Grand Army of the Republic in Keene, New Hampshire, on Memorial Day in 1884, Holmes gave a famous speech that tried to reconcile the generation of Americans that had so violently killed one another in the 1860s. According to Holmes, for both North and South, “the generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing.” Missing from the speech is any mention of why Americans were killing each other; missing is anything about slavery or racial justice. Though Holmes hated the way the Civil War was fought, he seems to have come to love war itself. Such attitudes won Theodore Roosevelt’s attention, and Roosevelt nominated Holmes to the Supreme Court in 1902.

In his long career as a judge, Holmes energetically rejected the idealism of his youth. For him, law rested on “experience,” not logic or morality. Holmes believed that experience had taught him that life was a Darwinian struggle, most clearly seen through the eyes of those like him who were “touched with fire” in wartime. Such attitudes were reinforced by a powerful American eugenics movement in the early twentieth century. An important footnote to Holmes’s Civil War service came in 1927 when the Supreme Court issued the infamous Buck v. Bell decision. Based partly on the badly flawed research of eugenicists, that ruling decided that surgical sterilization of people with disabilities without their consent was constitutional. Holmes wrote, “We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives.” The passage is a clear reference to the sacrifices made by soldiers, including his own and those of his dearest friends.

Dismissing sterilization as a “lesser sacrifice,” Holmes continued, “It would be strange if it [the public welfare] could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind… Three generations of imbeciles is enough.” A clearer example of heartlessness would be hard to find. “Touched with fire,” the idealistic optimism of the younger Holmes had long been burned away, one more casualty of the Civil War.

See the article on the Grand Army of the Republic for more information on that organization.

Sources:

- Buck v. Bell, Superintendent of State Colony Epileptics and Feeble Minded. (1927, May 2). LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- Colonel Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., of Co. A and Co. G, 20th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in uniform with sword. Silsbee, Case & Co., photograph artists, 299-1/2 Washington St., Boston. [1861-1865]. [Image]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- Arthur H. Estabrook, photographer. (1924). Carrie and Emma Buck at the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded. M.E. Grenander Special Collections and Archives. University at Albany. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- Harris & Ewing, photographer. Group at White House, including William H. Taft and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Washington, D.C.]. [1922]. [Image]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- Holmes, O. W., Sr. (1863). The Human Wheel, its Spokes and Felloes. The Atlantic Monthly, 11(67), 567–580.

- Howe, M. D. W. (Ed.). (1969). Touched with Fire: Civil War Letters and Diary of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., 1861-1864. Da Capo Press.

- Holmes Memorial. (1884, May 30). Keene, NH, before John Sedgwick Post No. 4, Grand Army of the Republic. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- Menand, L. (2001). The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.