Background Essay: How the Civil War Transformed Definitions and Experiences of Disability for Americans

Graham Warder, Keene State College

Many words about disability from history are offensive to us today. Thus it is essential to prepare students and to set clear ground rules about how they can respond respectfully when they encounter such words. See the Teaching Resource Time Out – Spotlight Offensive Language in Primary Sources.

A Quick Overview on Disabled Civil War Veterans

Neither the Union nor the Confederacy was ready for the start of the Civil War. They were especially unprepared to help injured and disabled soldiers. Before the war, the U.S. Federal Government simply did not provide care for any individuals in need. At the First Battle of Bull Run, July 21, 1861 the Union Army left many wounded on the battlefield when it retreated because it had no doctors or nurses, or even wagons to pick up injured men.

In the North, many Abolitionist women and some men reacted to this need by quickly mobilizing nurses, setting up hospitals, and organizing the U.S. Sanitary Commission to raise money to pay for care. As the war went on, the United States Government took over these services.

After the war the need continued. There had been 275,000 Union wounded. In an era when nearly all jobs required manual labor, disabled veterans could not work. Northern voters, especially Republicans, wanted to help the soldiers who had sacrificed so much to win the war. Veterans organizations, especially the Grand Army of the Republic, demanded and won the creation of a national system of hospitals and soldiers homes, and payment of pensions to disabled veterans. Union widows also got pensions. By 1900, the U.S. had paid nearly a million Union pensions.

Investigating the Story in Depth

Medical, Political, and Cultural Perspectives on Disability and the Civil War

Most historians recognize the Civil War as the most important turning point in American history. Yet how did the war affect American disability history? Ultimately, the Civil War radically transformed how Americans defined and experienced disability. Some changes benefited people with disabilities, but some changes were terrible.

Historians of the Civil War have long understood the conflict as a major turning point in medical history, as a crucial step in the modernization of American medicine as doctors achieved enormous advances in both surgical procedures and public health during and after war. Yet though medical context is crucial to understanding the experiences of people with disabilities, disability history is far broader and richer than the history of medicine alone. Similarly, historians of policy and government have recognized the Civil War as a first step toward the welfare state established by the New Deal in the 1930s. From the perspective of federal policy, the Civil War is often seen as a positive because it allowed for federal support of people with disabilities in a key early form of Social Security. At the same time, the Civil War also signaled a turning point in how Americans responded culturally to disability. The argument is simple: Before the Civil War, the dominant response to disability centered on pity and inclusion. Following the Civil War, the response to disability shifted increasingly to fear and exclusion.

The Second Great Awakening

Prior to the 19th century, people with disabilities generally received only whatever care and support their families could afford. Then, in the first half of the 19th century, Americans, especially from the Northeast United States, began to see disability, and much else, through the lens of the Second Great Awakening.

Religious fervor started with evangelical camp meetings like the one at Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801. It reached a fiery crescendo in places like Rochester, New York, with the revivals of Charles Grandison Finney. And it finally moved eastward to reshape the religious practices of New England’s Protestants. Most importantly, the new evangelical Protestantism of the Second Great Awakening was optimistic, rejecting the gloomy worldview of Calvinism. Spiritually inspired reformers were in the forefront of movements for the abolition of slavery, temperance (i.e. reducing the drinking of alcohol), and women’s rights. Many, such as ordained minister Frederick Douglass worked in multiple movements.

With the shift away from Calvinism also came a revolutionary change in how many Christians responded to disability. At the center of this change was a redefinition of affliction. In colonial times, affliction had been a punishment from an angry God or a test from a demanding God. With the Second Great Awakening, affliction became a spiritual opportunity for the non-disabled to bring the disabled into the religious community.

According to this goal of conversion, the non-disabled–that is to say, the fortunate–had to bring the Word of God to people with disabilities. New England was at the center of these efforts to reach people with sensory, cognitive, and psychiatric disabilities. In Hartford, the Congregationalist minister Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet supported the creation of American Sign Language and led the American School for the Deaf. In Boston, Unitarian Samuel Gridley Howe became the longtime superintendent of the Perkins School for the Blind. Throughout New England and beyond, Dorothea Dix, another Unitarian, lobbied, often successfully, for asylum reform for those deemed insane. And in Barre, Massachusetts, Hervey Wilbur, started the nation’s first “idiot school” for children with cognitive disabilities.

Antebellum Optimism–and Its Decline

The creation of the American School for the Deaf, which made possible American Sign Language and eventually Deaf Culture, was a group effort. Mason Fitch Cogswell, a physician, was a parent advocate. His daughter, Alice, was deaf, and he wanted her to somehow achieve literacy. Cogswell financed a trip by the Rev. Thomas Gallaudet to explore deaf education in Europe. Preferring French to British methods, Gallaudet convinced Laurent Clerc, a deaf man who had learned sign language at a pioneering school in Paris, to accompany him back to Hartford to teach at what would become the American School for the Deaf. Thus was born American Sign Language.

Gallaudet explicitly likened his efforts to those of a missionary. His stock fundraising speech, a sermon entitled, “On the Duties and Advantages of Affording Instruction to the Deaf and Dumb,” speaks of the needs of, “the heathen among us.” He argued that the deaf, not unlike “heathens” around the world, were a people bereft of access to God whose spiritual isolation could be broken with education. According to Gallaudet, “These are some of the heathen; — long-neglected heathen; — the poor Deaf and Dumb, whose sad necessities have been forgotten, while scarce a corner of the world has not been searched to find those who are yet ignorant of Jesus Christ.” In his efforts, Gallaudet necessarily promoted sign language as a means for conversion. For him, sign language was the original language, the language of the Garden of Eden, and thus close to God. Later in the nineteenth century, oralists would agree that sign was the original language. Yet for them, influenced by Social Darwinism, it was primitive and even apelike. They sought and almost succeeded in its destruction.

Another reformer in search of a mission was Samuel Gridley Howe. Long before joining militant Abolitionist John Brown’s Secret Six, and long before serving as an officer in the United States Sanitary Commission, Howe had volunteered as a doctor in the Greek War for Independence. Returning home from that romantic quest, he sought another. His next venture was to lead a newly created institution established to educate blind children from across New England. His most famous pupil was Laura Bridgman, the first deaf-blind individual to achieve literacy. (Early references to Helen Keller called her “The Second Laura Bridgman.”) Howe’s aspirations for Bridgman were utopian and ultimately unrealistic. He sought to use her as a widely publicized natural experiment that would prove that human nature was innately good. When she failed to live up to his perfectionist expectations, Howe, in the analysis of historian Ernest Freeberg, shifted his interpretation of blind people from one of romantic optimism to one of biological determinism. In a view that became more prevalent after the Civil War, Howe came to see people with disabilities as biologically inferior.

Dorothea Dix was another New Englander in search of a mission. After a bout of depression, she traveled to England and personally witnessed experiments in insane asylum management. She returned to Boston and set out to expose mistreatment and abuses in local jails and almshouses, and to promote new ideas of moral treatment. Moral treatment sought to nurture people with psychiatric disorders back to mainstream society by temporarily holding them in homelike settings. Dix had good intentions. Yet she promised overly optimistic results, including widespread cures of mental illness. As costs rose, and as asylums and hospitals grew quite large, conditions deteriorated. The main growth in size and declines in conditions came after the Civil War. Before the Civil War, asylum reform, like efforts associated with education of people with sensory disabilities, was grounded in the religious optimism of the Second Great Awakening.

Like many reformers, Dix volunteered during the Civil War. In her case, rising to United States Superintendent of Army Nurses. Howe, Dix, and many of the other reformers applied their institution-building skills to set up battle-field ambulance and medical services, and begin to establish hospitals and other long-term care. Frederick Douglass tirelessly recruited Black soldiers to join the Union Army, including two of his own sons. His eldest son, Lewis was permanently injured at the Battle of Fort Wagner.

Responses to the Sacrifices of Veterans

In some ways, all this antebellum optimism about disability was best expressed in an article by Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., published in the The Atlantic Monthly magazine in July of 1863, just before the Battle of Gettysburg. The famous Boston physician wrote about, “remarkable American Inventions”: prosthetics designed in response to the mass disability from the battlefields. “The limbs of our friends and countrymen are part of the melancholy harvest which War is sweeping down with… the patent reapers of Springfield and Hartford.”* Yet fear not, asserted Dr. Holmes, for technology giveth what technology taketh away. “While the weapons that have gone from Mr. Colt’s armories have been carrying death to friend and foe, the beneficent and ingenious inventions of Mr. Palmer have been repairing the losses inflicted by the implements of war.” Holmes claimed that American know-how would render disability moot. Meanwhile, the doctor’s son endured three grievous wounds and perhaps permanent psychic scars from that war.

Politicians, journalists, and historians have long used pictures of Civil War veteran amputees as symbols of the nation’s sacrifice. Among the most cited of these is this cartoon by Thomas Nast comparing an African American veteran standing next to Columbia with a throng of Confederate traitors. The cartoon asks who really deserves the right to vote.

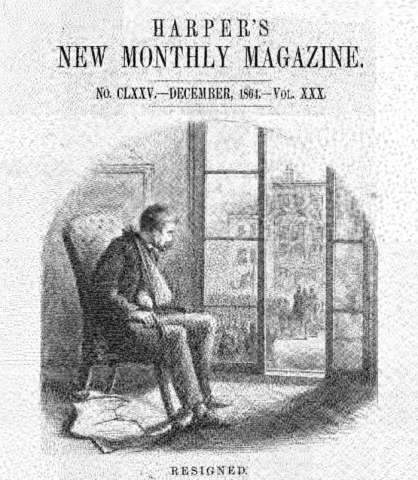

Less well known is a cartoon from Harpers Weekly. This disabled veteran is a potential problem and possibly someone to be feared. He looks out a window, possibly at a victory parade of “real” soldiers.

According to the accompanying poem:

Resigned

Crippled, forlorn and useless

The glory of life grown dim,

Brooding alone o’er the memory

Of the bright, glad days gone by;

Nursing a bitter fancy,

And nursing a shattered limb;

Oh, comrades, resigning is harder—

We know it is easy to die!

The veteran here is not a symbol of sacrifice; he is a threat. Americans must have wondered what would become of men like him. Some may have wondered how American society could be protected from such men.

One answer was soldiers’ homes. Like insane asylums, soldiers’ homes were supposed to be small, not the massive institutions that they became. Like Gallaudet and Dix before them, the Sanitary Commission did research on care for people with disabilities by traveling to Europe. The result was Sanitary Commission Report No. 49 which argued that Americans could best deal with the disabled soldiers of the Civil War by dispersing them into their local communities where they could be nurtured and cared for by kindly family and neighbors. According to the report, only a few foreigners, lacking natural American independence, would require institutionalization.

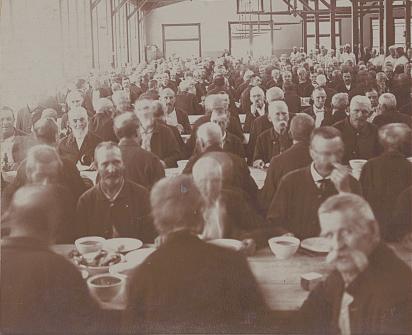

Yet things turned out very differently. By the late nineteenth-century, individual states had opened large institutions for needy veterans, and the largest of the National Homes, like the ones in Maine and Ohio, held thousands of residents. The abuse of alcohol in and around the soldiers’ homes became a national scandal and was investigated by Congress. The public, in the North at least, began to stereotype disabled Civil War veterans as tramps, beggars, and drunks.

Another large-scale response to Civil War disability was the pension system, which eventually became the largest item in the federal budget. Its cost would ultimately surpass that of the war itself. Pensions were initially only for widows and those severely disabled in combat, but as time went on, access eased, and payments increased. By the 1890s, old age itself essentially became a disability, and all Union veterans qualified. The Republican Party was the primary proponent and political beneficiary of these changes. The huge veterans organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, in particular became a powerful lobby for pensions and homes. Far more generous than European military pensions, the vast federal pension system was labeled “socialism” by its opponents, especially Democrats.

A Dark Period for Disability

Ultimately, the Civil War ended antebellum notions of disability. In some ways, the scale of the Civil War simply overwhelmed religious and moral definitions of disability and the capacity of Christian benevolence to effectively respond to it. Instead, disability was redefined as a national political issue. Some believed that disabled Union veterans, the nation’s citizen soldiers, were owed a debt, and that debt was owed not just to veterans with visible disabilities like amputees but also to the far greater number of veterans with invisible disabilities, with labels including, “melancholia,” “acute mania,” and “soldiers’ heart.” Disability became increasingly medicalized because of the Civil War as doctors increasingly asserted their cultural authority. And disability was extensively bureaucratized.

By the turn of the twentieth century, national debates on disability merged with the increasingly powerful eugenics movement. The transformation of one influential veteran hints at how this took place.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., son of the doctor discussed above, came close to death several times during the Civil War. He survived and even lived a long life, first as a sort of professional veteran and strenuous proponent of a reconciliationist memory of the Civil War, then as a longtime Justice of the Supreme Court. His most famous–or infamous–case would be Buck v. Bell, delivered in 1927. The case, never overturned by the Supreme Court to this day, declared involuntary surgical sterilization for eugenic purposes constitutional. Holmes claimed a “menace” of people with cognitive disabilities if released and allowed to have children. In a passage clearly referring to his experiences in the Civil War, he wrote:

- “We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.”

This was a low point for people with disabilities in an era of lows. Before the Civil War, disability represented a spiritual opportunity for the non-disabled, a chance to prove one’s own moral worth and to move the nation one step closer to the Kingdom of Christ. Pity fostered inclusion. After the Civil War, disability became a social, economic, and even a biological burden, then a threat. Fear brought exclusion.

Pity and inclusion ironically allowed greater opportunities for self-determination and self-definition for people with disabilities. The development of Deaf Culture, though Gallaudet never foresaw it, is a primary example of this.

Responses rooted in fear and exclusion were far more constraining and oppressive. Large institutions, impersonal and sometimes brutal, no matter how humanitarian and utopian their original intentions, were designed to deny people with disabilities any possibility of agency. The casual cruelty expressed by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in Buck v. Bell is a primary example. The titanic struggles of the Civil War prepared decision makers to think in Darwinian terms of national policy and cultural survival. For a century, the implications of this were profoundly destructive for people with disabilities.

Sources

- NPS fact sheet. Civil War Facts: 1861-1865. National Park Service.

- History of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. National Park Service.

- (1845). Frederick Douglass. Engraving. Library of Congress.

- (1864). Resigned. Harpers Magazine. Internet Archive.

- (1864). Pardon. Franchise Columbia. Nast, Thomas. Harpers Magazine. Library of Congress.

- (1865). Washington, D.C. Company I, 10th Veterans Reserve Corps, at Washington Circle. Library of Congress.

- (1901). Dining room, Soldier's Home, Dayton, Ohio. R.R. Whiting. Library of Congress.

- (n.d.). Dorothea Lynde Dix. Library of Congress.

- (n.d.). National Archives. Military Resources: Links to military reference material, military history and research, and to specific topics.

* See the online exhibit The Springfield Armory: Forge of Innovation.