In the decades following the Civil War, the sight of armless or legless men on the streets of America was common. Though some amputations resulted from industrial accidents, most amputees were veterans who had lost limbs in battle. Because of the large size and slow speed of Civil War bullets, called Minié balls, soldiers unlucky enough to get hit felt their flesh shredded and bone shattered. Given the lack of antibiotics or even basic knowledge of germ theory, the only way a surgeon could save a life was often to remove a limb.

Antebellum prosthetics were little more than hooks and pegs. Disabled veterans could expect to be at the front of the line when government jobs, like those at post offices, were doled out. The 1865 cartoon in Franklin Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, intended to be humorous, captured the common expectation that men who had lost hands would soon be fitted with hooks.

Men ultimately were fitted not with hooks but rather with more realistic looking prosthetics. After the Civil War, the prosthetics business boomed, and the federal government was key to paying for the growing industry. The visibility of such disabilities encouraged government action. Like the money spent on pensions and soldiers’ homes, public funds to benefit prosthetics manufacturers were usually viewed as just compensation from a thankful nation for sacrifices on the battlefield.

Expectations that men could be remade were high. As Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., wrote in 1863, “It is not two years since the sight of a person who had lost one of his lower limbs was an infrequent occurrence. Now, alas! There are few of us who have not a cripple among our friends, if not in our own families. A mechanical art which provided for an occasional and exceptional want has become a great and active branch of industry. War unmakes legs, and human skill must supply their places as best it may.” Dr. Holmes believed that “the melancholy harvest” of war would be solved by the inventions of men like Benjamin Franklin Palmer of Philadelphia.

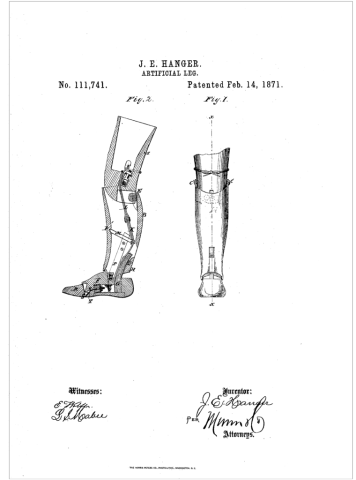

Palmer, an amputee who started his business in 1846 in New Hampshire, was the most famous and successful prosthetics manufacturer of the era. He held five U.S. patents for artificial limbs. Palmer, and his fellow artificial limb manufacturers, called on the federal government to repay a debt to those who had prevented the “dismemberment” of the nation. Some manufacturers like Palmer, A.A. Marks of New York, and James E. Hanger grew rich. They presented themselves as servants of public welfare more than as profit-seekers. Yet, profit and innovate they did. The U.S. Patent Office approved 150 patents for artificial limbs and assisting devices between 1861 and 1873. By 1870, the federal government had paid out half a million dollars for 7,000 artificial limbs for Union veterans.

Confederate veterans had to rely upon the Southern states, which were diminished by the war. Confederate veteran and amputee James E. Hanger started a company in Virginia to manufacture prosthetic limbs. His highly successful company is still in business today.

Advertisements for prosthetics were at times worthy of the “Age of Barnum.” In Palmer’s pamphlet encouraging federal spending on his artificial arms, Will the American Government Present an Artificial Arm (Not a “Clutch”) to the Mutilated American Soldier?: Petition of Three Hundred Soldiers, disabled soldiers lauded Palmer’s invention as both realistic and functional. One wrote, “The hand I am perfectly satisfied with; I can do anything I expected to do with it, and a great deal more; in fact, I can do almost anything.” Another, referring to the masculine job of directing a team of horses, wrote, “In driving, of which I have a great deal to do, I grasp them almost as firm as with the natural hand.” He went on, “in eating, I use the fork with the greatest facility.” Other pamphlets advertised artificial legs with assertions that men with prosthetic legs could now easily dance with their sweethearts. Manliness had been returned to them.

In reality, such prosthetics, constructed of wood, leather, and rubber, were heavy and unwieldy. Many men found hooks more useful. Palmer’s artificial arms and legs were designed to disguise a disabled veteran’s disability. Returning “manliness” meant responding to the gaze of others. They were far less a functional assistive technology.

An image by Winslow Homer published in Harper’s Weekly just after the war captures the anxiety around gender roles that disabled Civil War veterans must have experienced. In the print, a veteran who has lost an arm sits in a carriage looking distraught. It is the woman who drives.

Sources:

- John January of Illinois, who had lost his feet to scurvy and gangrene while a prisoner of war at Andersonville, ca 1890. Photograph by W.E. Bowman. Library of Congress.

- Douglass, Darwin DeForrest. The Douglass Patent Artificial Limbs. Springfield, Mass.: Bowles & Co., 1865. Internet Archive.

- J.E. Hanger. U.S. Patent 111,741. (1871). Artificial Leg.

- Hasegawa, Guy R. Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012.

- Herschbach, Lisa. “Prosthetic Reconstructions: Making the Industry, Re-Making the Body, Modelling the Nation.” History Workshop Journal, no. 44 (Autumn 1997): 22–57.

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell. “The Human Wheel, Its Spokes and Felloes.” The Atlantic Monthly 11, no. 67 (May 1863): 567–80.

- Winslow Homer, “Our Water Places – The Empty Sleeve at Newport,” Harper’s Weekly, August 26, 1865.

- Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. “Result of Appointing a Veteran as Postmaster,” February 11, 1865.

- “Maimed Men – Life and Limb: The Toll of the American Civil War." (n.d.). U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Palmer, Benjamin Franklin. Will the American Government Present an Artificial Arm (Not a “Clutch”) to the Mutilated American Soldier?: Petition of Three Hundred Soldiers. Philadelphia, 1863.