Peek into the daily life of this community of radical reformers

Meet NAEI members, James and Dolly Stetson and their six children, revealed through a touching and inspiring four-year exchange of letters.

Explore the work and influence of the Northampton Association of

Education and Industry (NAEI) in 1842-1846 through more than 70 historic pictures, maps, letters, newspaper articles, speeches, book excerpts, advertisements, and other primary sources. Video and hands-on exhibits animate key characters, places, and concepts in this important page in U.S. history.

UTOPIANISM: CREATING AND LIVING RADICAL CHANGE

In 1842, seven men formed a utopian community in western Massachusetts, called the Northampton Association of Education and Industry. The founders, a mixed group of abolitionists, farmers, and silk manufacturers, supported William Lloyd Garrison and the immediate abolition of slavery and wanted to join together with others who shared these beliefs.

The Association turned to a bankrupt silk mill in present-day Florence, MA to support its members. The community planned an egalitarian enterprise around silk manufacturing following a popular movement of the 1830s and 1840s, which aimed to reverse the regional decline in farm income. For Association members, silk was both practical and ideological—it did not depend on slavery, and labor to make it could be shared among men, women, and children. The Northampton Association quickly became a hotbed of radical abolitionism, religious reform, and democratic experimentation.

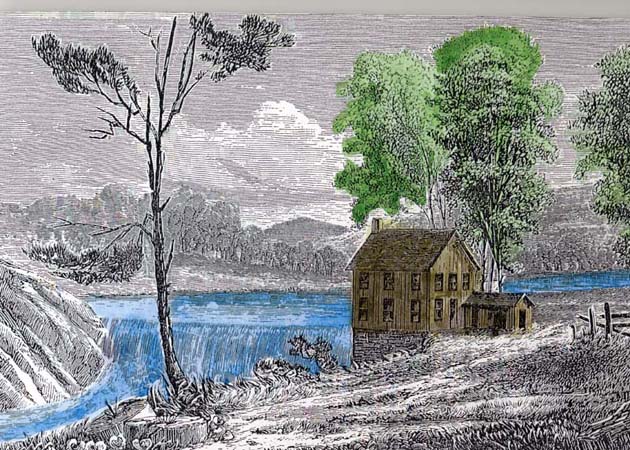

Samuel Whitmarsh turned an old oil mill in Northampton into a silk mill in the early 1830s.

Samuel Whitmarsh turned an old oil mill in Northampton into a silk mill in the early 1830s.

During its existence, the community attracted national figures including Sojourner Truth, William Lloyd Garrison, David Ruggles and Frederick Douglass. During the four-and-a-half years of the Association, over 200 people would join the community, living out their beliefs in equality and fair economic principles. Despite its short tenure, the story of the Northampton Association provides a window into a key strategy of some early nineteenth century reformers.

It demonstrates the intersection of several concerns shared by members of utopian communities: how to run a society based on the principle of equality, how to survive economically in an industrializing society, and how to create a truly democratic government. The choice to join a community like the Northampton Association may have been radical, but the issues the members grappled with were at the core of American society.

THE STETSON FAMILY

The community was comprised of mostly white families and individuals who joined because of personal connections to existing members. People were also drawn to the Association because of its radical reform ideas. Among these members were several families from Brooklyn, Connecticut, including James and Dolly Stetson and their six children, Almira (15), Mary (12), Ebenezer (10), Sarah (8), George (7), and Lucy (2). Dolly gave birth to a seventh child, James, less than a year after arriving at the Association.

silk factory for the Northampton Association.

Moving to Northampton was a big change for the Stetson family, yet the Association represented many of the Stetsons’ ideals. James and Dolly were heavily involved in the abolitionist movement. Their network of anti-slavery contacts expanded when William Lloyd Garrison married Helen Benson. Helen’s brother, George Benson, was a founder of the Northampton Association and James Stetson’s brother-in-law.

After the Bensons and several other neighbors joined the Association, it seemed even more attractive to the Stetsons.The community also offered James an alternative means to provide for his family. He owned a shop, making chaises and harnesses, but it was never a lucrative business, and the family often faced hard times. Benson suggested James would be the perfect person to peddle the Association’s wares from their silk mill. Although James Stetson was uncertain about the stability of the Association’s business venture, they were convinced the community’s religious principles and commitment to education would offer a better upbringing for the Stetson children.

During their stay at the Association, Dolly and the children wrote James frequent letters while he was on the road. Now, this collection of seventy-five letters is the major source of information about daily life in the community.

THE STETSON LETTERS AND NAEI DOCUMENTS

The Northampton Association of Education and Industry provides a small window into an era of fervent reform in 1840s America. Within the Association’s rich documents, lies a wealth of information about the local and national history of the era.

This website looks to use the personal letters of the Stetson family and local documents to illuminate the broad historical issues of the time, which centered on various reforms including abolitionism, non-resistance, temperance, and education reform. The rich nature of the included letters creates a personal narrative, bringing to life the “utopian” era– the personal correspondence humanizes and complicates the communitarian moment and its often oversimplified history.