First of all our “convention” is a small affair in point of numbers to what was anticipated, and those that are here are more Abolitionists than Associationists… the principle matter of debate this morning was the slavery of the north and south compared—Garrison objected to the term slave being applied to us at the north—N.P. Rodgers contended that we were are all slaves and that we must emancipate ourselves before we could do anything efficiently for them of the south.

June, 16th, 1844

Strands of Abolitionism

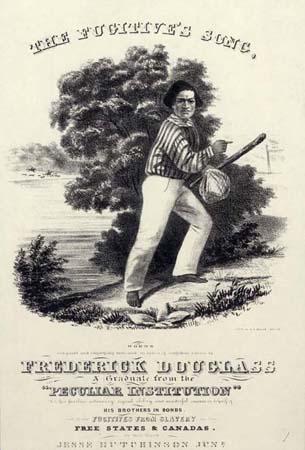

speaking about his experience as a fugitive slave.

The members of the Northampton Association filled their lives with educational, political, and religious discussion — Abolitionism being a main focus. Association members engaged in continued debate over how to make their model for America perfect, though they all clearly agreed on the need for the immediate abolition of slavery.

The 1840s was a decade of fervent reform in the Northeast. Reform movements including temperance, abolitionism, educational reform, and expanded democracy thrived, revealing reformers’ concerns about the direction of American society. As one of the most prominent reform movements, abolitionism generated passionate debate, some of which played out in western Massachusetts. The Northampton Association was intimately involved in the continued development of the anti-slavery movement.

During the antebellum period in America, the slavery debate was more complex than a simple split between those who supported it and those who opposed it. The majority of northerners were indifferent to the existence of slavery in the south. Yet the expansion of slavery into the Mexican Cessionstirred a much more animated debate.

By the 1850s most northerners were anti-slavery expansionists, rallying around the Free Labor idea of the Wilmot Proviso, which proposed the banning of slavery in the Mexican Cession. The expansion of the factory system and the establishment of a market economy made northerners more reliant on the slave-based cotton production of the south. Those who called for the complete abolition of slavery made up a small percentage of northerners.

Those who considered themselves abolitionists also differed in their views about how and when that freedom should take place. Opponents of slavery ranged from moderates, who wanted gradual emancipation, to those – including the members of the Northampton Association – who demanded the immediate abolition of slavery.

The Second Great Awakening sparked a movement led by William Lloyd Garrison which identified slavery as a sin—his movement calling for the immediate abolition of this inhumane institution. Garrison began the American Anti-Slavery Society and its local branches organized northerners around immediate abolition and condemned the government for supporting slavery. Garrisonian radical actions included burning the Constitution as a pro-slavery document and advocating for non-resistance and even disunion.

Garrison also took a firm stance on women’s participation in the abolitionist movement. In his pursuit of democratic principles, he believed that women should have a prominent role in reform. This caused a rift among abolitionists since many in the anti-slavery movement viewed his behavior as too radical. Eventually a second rift in the divided reformers. Many abolitionists believed that political action was more practical than the religious and moral radicalism of Garrison. These reformers formed the Liberty Party in 1840.

Escaped slaves and free blacks were among the most vocal in the abolitionist movement. Former slaves like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth could speak (as they did at the Association) of the personal experience of slavery—their narratives convincing northerners of the brutality of the slave system. Black leaders, such as, Harriet Tubman, David Ruggles, Sojourner Truth, and William Still worked to assist fugitive slaves escaping to free territory. Abolitionist newspapers, like the Liberator and the North Star were used to organize reformers and inform northerners on the issues of slavery.

Abolitionism and the Northampton Association

The Northampton Association began and ended (1843-47) in the heat of Abolitionist fervor, immediately before the country began a fast-moving downward spiral toward Civil War. The 1840s was filled with reform movements, economic change, and growing sectional divide—all of which took a prominent role in the daily life of association members.

The Stetson letters provide a window into their sense of optimism for change in America. (see letters about staying to change 17, 47) Later, during the 1850s the Abolitionist movement would move to the forefront of all other reforms as slavery and its expansion would become the center of political, social, and economic debate across the nation.

The Association’s dedication to expanded democracy and abolitionism allowed women to participate in the reform debate and welcomed black members into the community. Although it will never be known how many fugitive slaves may have passed through the community, there were a few African American members who remained members for a significant stay.

Sojourner Truth, David Ruggles, Stephen Rush, and George Washington Sullivan were the four black members who lived at the Association for any extended time. Limited information is known about Rush and Sullivan, but Truth and Ruggles played prominent roles in the community and in the national abolitionist movement, as well as in the letters of Dolly Stetson.

Truth lived at the association with her daughters and directed the laundry department. Almira Stetson frequently wrote of Truth’s stringent moral code which often focused on the pastimes of the children at the Association. Truth was a valued worker. Her image as moralistic and evangelical is much more prominent than in the Narrative of Sojourner Truth and other modern portrayals. Truth’s stay at the community was in the beginning of her career as an activist as she would soon after become the very public feminist and abolitionist known by most Americans. Her popular Narrative came out somewhat later, in 1850.

Ruggles, an African American printer and major leader in the Underground Railroad, also resided at the community. Later he developed his water-cure (64) facility based on the practice of hydropathy in Northampton. His water-cure methods were used at the community to treat ailments including Almira’s chronic pain from a fall she took in the cocoonery. The limited number of African Americans seems to be most tied to the fact that membership at the community was most commonly linked to familial and social connections.

The members of NAEI continued to educate themselves about slavery and continued to debate its current issues. The Association regularly hosted lecturers who spoke out against slavery including Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, N.P. Rogers (11, 47) and others. They addressed both southern and northern involvement in the slave system, and debated what methods would be best to combat slavery’s impact on society. Dolly frequently references the Liberator (75) within her letters and keeps James informed about lectures, meetings and discussions on slavery held at the Association.

The Stetson family was clearly dedicated to abolitionism prior to their involvement in the Northampton community. Dolly played a major role in starting Connecticut’s Brooklyn Female Anti-Slavery Society, of which she was president for five of the six years of its existence.

The Stetsons had supported the establishment of the New England Anti-Slavery society which later became the American Anti-Slavery Society led by Garrison. Many in Connecticut disapproved of the actions of the Stetsons and other radical abolitionists, in the same way the Northampton community would disapprove of the NAEI’s extreme views and actions. Their commitment to come-outerism, non-resistance, and even discussion of disunion isolated them from most Americans and even from many abolitionists.

Throughout the Stetson letters, there is rich debate over slavery and Frederick Douglass visited the community and praised its feeling of equality, commenting on the lack of class and racial divisions. (Also commenting on its Spartan living conditions.) William Lloyd Garrison visited the community on several occasions speaking, participating in conferences and visiting relatives. (George Benson, one of the founders, was Garrison’s brother in law.)

Most of the Stetson family letters traveled via boxes of silk products that were sent to James to be sold in Boston and other surrounding areas. The descriptions of their contents, deliverers, and recipients show a network of abolitionists upon whom the community relied to support their silk business. The choice to produce and sell silk was partially to move away from cotton and promote a non-slave industry. Several of Almira’s poignant letters to her father show her knowledge of Abolitionism and women’s rights—especially her desire to follow and emulate the female leaders of the movements like the Grimke sisters and Abby Kelly (39, 42).

The Stetsons and their fellow associationists were staunch believers in extending freedom to more Americans. The Stetson letters are full of meaningful references to Abolitionism, famous abolitionists and the debate that would soon be overwhelming the nation. The Association’s saw their higher purpose as closely tied to the moral troubles they saw in slavery—a society free of class, race and sex restrictions was central to their vision for the future.