The Steamboat Barnet: Emerging Industrialism

The Connecticut River, now largely abandoned for economic purposes, once played a vital role in the commerce of New England, and served as a major stimulus to cities along the river. For more than two centuries, it functioned as the only lifeline for the small rural settlements where farmers along its banks tilled rich valley soils.

Throughout the colonial period, when few passable overland roads existed, the river and its tributaries unified the region, linking small Vermont and New Hampshire villages to the larger communities of Northampton and Springfield. During the winter months, when the river was frozen, it served as a highway for wagons and sleds.

Throughout the remainder of the year, except in the spring when the ice was breaking up, farmers and merchants used the river to transport goods locally, from town to town, and as a link to distant markets.

The primary means of shipping goods up and down the river was the flatboat. These crafts could be very large, and often employed a mainsail located in the middle of the boat. When the wind was inadequate, “polemen” propelled the flatboat forward. Spearing the bottom of the river with a 12-20 foot pole, a poleman would walk the length of the boat, pulling the boat along the surface of the water.

After the Revolution

After the unsettled years of the Revolution, the population in the Connecticut River Valley steadily increased, and the need for more efficient transportation grew accordingly.

Although the region remained largely rural, and exports still consisted primarily of agricultural products, particularly tobacco, Springfield, Northampton, and Hartford took on more and more of the characteristics of small cities.

From 1790 to 1820, Springfield almost tripled in size, growing from approximately 1,600 to almost 4000 inhabitants.Fish were abundant in the river and fishing, an important business, boosted trade. Fishermen harvested huge numbers of shad and herring, and shipped surplus salt cod to the West Indies where it was a staple of slaves working on sugar plantations. Brandy and gin were also vital to the West Indies trade. This business became so important to the region that by 1810, there were approximately 125 distilleries in Vermont alone.

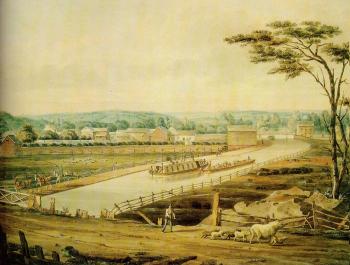

Logging was also important. Woodsmen floated rafts of logs down the river from Vermont and New Hampshire, providing shipbuilders with lumber in the many yards in towns along the lower river (below Hartford). In Springfield shipyards regularly built vessels as big as ninety tons. Although shipment of goods by flatboat continued until well after the Revolution, there was a growing demand for improvements in the boats that transported goods and people. In addition, falls and rapids slowed travel up and down the river. On the upper river the greatest obstacle to navigation was the South Hadley Falls, just north of Springfield. At this location, the river dropped fifty-five feet over more than a two-and-a-half mile length. These falls were so disruptive to shipping that twenty-two local businessmen met in 1792 to form the “Proprietors of the Locks and Canals on the Connecticut River.”

These business leaders, primarily from Springfield, Northampton, and Deerfield, engaged Ariel Cooley, a Chicopee engineer, to construct a canal. On April 16, 1795, the first commercial vessel passed through the canal.

The success of the South Hadley system inspired the development of additional canals. In 1800, a canal opened at Turners Falls, and this was followed by three systems in Vermont at Bellows Falls (1802), Summers Falls (1810), and White River Falls (1811). Finally, the “Proprietors” opened a canal at Enfield, Connecticut (1829). With this system of five, and later six canals in operation, trade along the river dramatically increased. Flatboats were soon transporting large quantities of iron, millstones, West Indies molasses, and rum up the river, while farm products, potash, lumber, and maple sugar went down the river.

Along with developments in the lock and canal system, early nineteenth century business and government leaders invested in the construction of new bridges and turnpikes. They hoped that the combination of canals and new or improved overland transportation routes would facilitate trade in the region. The first bridge across the Connecticut River was dedicated in 1805, connecting West Springfield to Springfield. Private companies built additional smaller bridges. These bridges increased the flow of people and goods back and forth across the river.

The need to improve highways spurred several major turnpike projects. Between 1797 and 1803 about twenty corporations built turnpikes that linked various western Massachusetts towns. Users did not consider the tolls for traveling these roads a major burden because the new roads encouraged trade and greatly reduced travel time. And, by mid-century, the towns had taken over most of these roads and eliminated the tolls.

At the same time merchants and civic-minded leaders were taking steps to improve roads, bridges, and navigation on the river, others were seeking ways to improve the vessels. The expansion in trade had placed greater demands on the shipping and transportation sector, and valley entrepreneurs recognized that the flatboat was simply too inefficient and slow to meet their growing needs. Enterprising individuals began to experiment with the steam engine.

The Era of Steam

The first successful application of the steam engine was in 1787 when John Fitch, originally from Windsor, Connecticut launched a steam-powered craft on the Delaware River. This was followed by the work of Samuel Morey of Orford, New Hampshire, who developed a steamboat that traveled between Orford and Fairlee, Vermont in 1792.

Morey’s boat was the first to ply the waters of the Connecticut River, and his initial success inspired further development. A few years later, he developed a sternwheeler that traveled from New York to Hartford, but Morey was not a shrewd businessman and could not get the financial support he needed to make his operation successful. Although Morey was granted several patents relating to his work on the steam engine, it was Robert Fulton who made the steamboat a commercial success.

The first commercial steamboat to find employment on the Connecticut River was the Julianna, which began passenger and shipping service between Middletown and Hartford in 1813. Steamboat travel was fast. The Julianna was capable of traveling from Hartford to Middletown in just three hours; it could make the trip back up the river in four and a half hours. In 1822, William C. Redfield of Cromwell, Connecticut, incorporated the Connecticut Steamboat Company to finance the development of steamboat operations on the river.

The success of steamboat companies in the early 1820s established the commercial feasibility of steamboat operation on the lower Connecticut River. Yet, due to the Enfield rapids, no steamboat had traveled north of Hartford.

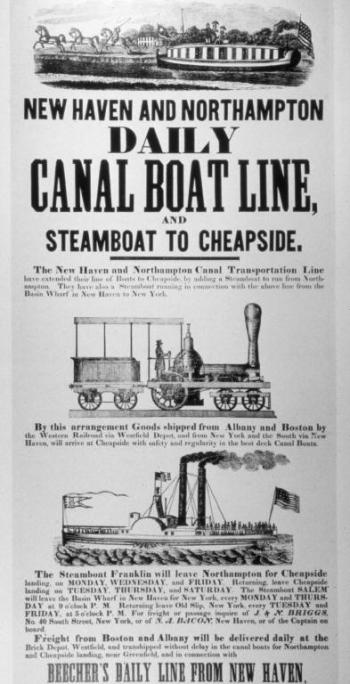

This would soon change in response to a new commercial threat. In 1822, New Haven merchants who hoped to steal some of the river traffic from Hartford obtained a charter to build a canal from New Haven through Farmington and on to the Massachusetts border, where it would connect with the Hampshire-Hampden canal to Northampton. If the New Haven canal proved successful, it would be a big threat to the business interests of Springfield and Hartford.

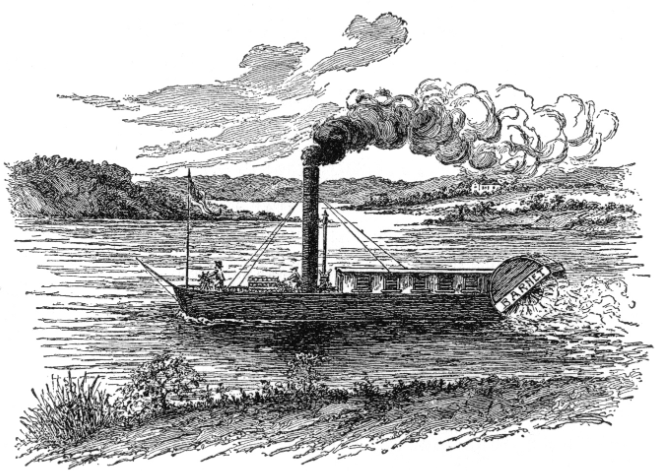

The Steamboat Barnet

This spurred Hartford business leaders to look for ways to develop river transportation above the Enfield rapids—and one solution was to build the Barnet. In 1824, the Connecticut River Company commissioned Brown and Bell of New York to build a steamboat that could navigate the rapids between Hartford and Springfield. Brown and Bell completed the vessel in August of 1826, and by mid-November they installed the engine. The Barnet was ready for its maiden voyage.

On November 17, the sternwheeler set out from Hartford with Captain Roderick Palmer at the helm. All went well until the steamboat reached the Enfield rapids. The Barnet began to climb, but the combination of an unfavorable wind and insufficient power prevented it from making it through the rapids. The engine was strengthened and polemen attached flatboats to each side to assist the Barnet through the rapids.

This time, with the combined power of thirty polemen and a stronger engine, the Barnet negotiated the rapids and continued up the river. When the Barnet steamed into Springfield almost everybody in town ran down to the river to see it.

At this point, the story of the Barnet is vividly captured in the letters of William Lathrop, who was living in West Springfield and witnessed the maiden voyage. Lathrop was intimately connected to the life on the river and in the valley. He was born in West Springfield and raised in one of the most prominent families of the Connecticut Valley. His grandfather, the Rev. Joseph Lathrop, who dedicated the first bridge across the river, graduated from Yale College and had served as minister of the First Congregational Church of West Springfield for sixty-three years. William’s father, Samuel Lathrop, was an important state and federal political leader.

Lathrop described the Barnet’s voyage over three days. When the steamboat reached Bellows Falls on December 12, the captain determined that the vessel was too wide for the locks, and it had to turn back south. The Barnet had failed to reach the town of Barnet, but her advance this far north proved that commercial steamboat operations were possible in the upper river.

The success of the Barnet assured Springfield and Hartford merchants and traders that their cities would continue to grow. It also inspired entrepreneurs to develop the full potential of steam power. Meanwhile, the New Haven merchants whose commercial rivalry had motivated Hartford and Springfield business leaders to develop the steamboat on the upper river finally completed their canal in 1834.

It opened for business in June of 1835, but in its first three years of operation it lost over $140,000. In spite of the Barnet’s triumph, the commercial viability of steamboats was brief. The development of the railroad was just around the corner. As early as 1830 Massachusetts granted the first charters to several railroad companies to develop lines out of Boston.

By the mid-1840s, the rail network had clearly trumped steamboat shipping. By 1850, the number of passengers traveling on the rail line from Boston to Albany was over 500,000. In less than two decades, steam-powered river transportation and the system of locks and canals gave way to new technological developments completely unforeseen in the days of the Barnet.