UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR LEARNING FOR SOCIAL STUDIES

The philosophy that educational excellence is achieved by offering multiple paths to understanding is vividly illustrated by the talk by L. Todd Rose called The Myth of Average.

To make the learning of History and Social Studies accessible for all, educators have increasingly built upon the research program of CAST, the organization that first articulated and developed the framework of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Primary sources—including from the Library of Congress—offer distinctive, powerful, flexible tools to expand choices and means of access that support and mesh well with UDL principles.

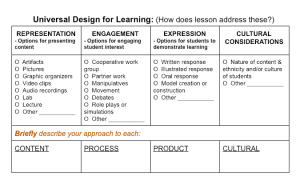

Minarik & Lintner, p. 45. Adapted from Glenna Gustafson and Tamara Wallace, “Radford University Lesson Planning Template with UDL,” 2010.

Minarik & Lintner, p. 45. Adapted from Glenna Gustafson and Tamara Wallace, “Radford University Lesson Planning Template with UDL,” 2010.

UDL draws upon brain-based research on learning to encourage educators to provide multiple means of engagement, representation, expression and action for all students. (A good place to start is CAST’s detailed graphic explaining the three principles: UDL Guidelines.)

Emerging America courses employ a UDL + Cultural Considerations checklist as a lesson plan design tool (see box) from Darren Minarik and Timothy Lintner’s excellent book, Social Studies and Exceptional Learners, published by the National Council for the Social Studies. (2016). Their checklist reminds us to incorporate all three elements of UDL, with a fourth element, “Cultural Considerations.” Find many examples of accessible lesson plans with checklist completed in our library of Teaching Resources.

Reform to Equal Rights: K-12 Disability History Curriculum describes specific UDL strategies in all 23 lessons. Unit plans each include an overview grid for that unit.

Engagement

in Lowell, Massachusetts.

Mario Monteno. 1987.

Library of Congress.

https://www.loc.gov/item/awhbib000060/

Students engage with course content in many ways. Deepen ownership and engagement through personalized content, a variety of classroom activities, thoughtful attention to the size and structure of learning groups, access to authentic community resources, and especially through student choice.

Note that while choice of activities is vital, many students need for their choices to occur within consistent, repeated classroom routines. Always present clear goals and instructions, and provide timely and focused support.

Select topics and materials with intrinsic student interest, such as:

- primary sources that feature voices, perspectives, or experiences of young people (journals, newspaper accounts, photos, or artwork)

- topics connected to current events

- questions and topics with flair

Personalize content to maximize student interest:

- topics of study that have cultural relevance to the student’s own environment, heritage, location, or situation

- topics or sources in an area of interest or mastery of the student

Include experiential activities:

- Students pair up to analyze sources, and complete reports in graphic organizers.

- Small groups of students rotate between stations in the room to examine a variety of primary sources.

- Individuals, pairs, or teams conduct research on independent projects–with strong and directed teacher support where needed.

- Groups or the whole class researches and plans service-learning and civic engagement projects to address real community needs.

Model Lesson for Engagement: In Puerto Rican Identity, students examine documents and other primary sources showing various generations of Puerto Ricans engaging with Anglo-American culture while preserving their cultural identity.

Cultural Considerations:

An essential facet of engagement is to ensure that materials and approaches are culturally relevant for the particular students in your classroom.

- Culturally Relevant Pedagogy Using Primary Sources instructional videos from the Minnesota Historical Society:

- Overview (with intro) (10:05 min:sec)

- Motivating Students toward Success (with intro) (9:11 mins.)

- Tap Students Cultural Competence (with intro) (9:04 mins.)

- Examine the Status Quo (with intro) (10:10 mins.)

Representation

Educators who follow Universal Design for Learning principles provide multiple ways to represent concepts to students of differing ability levels. When working with primary sources, teachers present a variety of sources and employ varied tools to examine them.

Dorie Miller received the Navy Cross

at Pearl Harbor. David S. Marin. 1943.

Library of Congress.

https://www.loc.gov/item/93505848/

Primary source representations can include:

- Text passages (with related translations and transcriptions)

- Forms or government documents

- Personal narratives and letters

- Newspapers, books, and reports

- Maps and blueprints

- Photos, paintings, drawings

- Cartoons and posters, including symbolism and captions

- Sound recordings of interviews or of songs

- Real artifacts from the past or reproductions of tools, household goods, or personal items

Secondary sources and teaching techniques help vary representation:

- Teacher presentations, with or without audiovisual aids

- Text presentation, including textbooks, non-fiction books, period fiction and poetry, or historical novels

- Produced audio and video, with mix of sounds and images (podcasts, films)

- Maps, including conceptual maps as well as a variety of geographic formats

- Graphic organizers that use text and groups of lists

- Manipulative models and representations (for example: laminated shapes placed on maps, color coded to represent categories of data)

- Whole-body activities, such as standing in groups to represent economic data, or acting out a courtroom scene

- Graphic organizers that use spatial relationships, diagrams, and aggregate charts.

Data, Information, Concept,

Strategy, and Metaphor visualizations.

Ralph Lengler & Martin J. Eppler.

www.visual-literacy.org

Making Classroom Participation More Equitable With Hand Gestures - Edutopia.

Model Lesson for Representation: Japan's Attack on Pearl Harbor uses oral histories from the Japanese Internment Camps and a mix of maps and other documents to examine American reactions to the Pearl Harbor bombing.

Resources for Representation:

Tools and approaches for Representation are woven throughout the EmergingAmerica.org pages on Disability History through Primary Sources, Assistive Technology, and Inquiry Strategies.

Thinking Maps by David Hylerle presents a coherent strategy for developing and using graphic organizers that supports learning across grades and subjects.

The Periodic Table of Visual Representation Methods chart links to dozens of options for graphic presentation. See the options in list form here.

Creek, J. (n.d.). “How to Make an Infographic” Videos & step-by-step guide. Periodic Presidents.

Action and Expression

The critical element is to create alternatives that allow students to show different strengths and to pursue paths around barriers to understanding and expression.

Ensure that assessments offer choices of mode and–where possible–of subject. See options for Assessment. Developing alternatives–and additions–to expository writing as the default means to communicate learning in History and Social Sciences enhances learning for all students. Students need opportunities to express themselves in written and spoken word, visuals, movement, objects, and technology. Primary sources can stimulate thinking and broaden means of expression.

Alternative forms of expression of learning might include:

- drawing simple (or elaborate!) comic strips or graphic novel pages

- preparing skits, radio-play episodes, or talking tableau presentations

- writing diary entries or letters in the persona of an individual from the events being studied

- creating annotated maps or diagrams showing places or events under study

- preparing posters or political cartoons that advertise, educate, dramatize, or persuade

- creating a data summary (weather data, population data, widows pension applications, number of ships, etc.)

Action is a powerful catalyst to learning, and incorporating movement and gesture into lessons can improve student engagement and learning outcomes. (See the research base in "How Movement and Gestures Can Improve Student Learning.")

Students hunger for means to have a voice and an impact on their world. Help students to learn the skills and dispositions of civic engagement through Civic Engagement Projects. And explore the options for service-learning projects, such as our own Windows on History project.

Model Lesson for Expression: In Monuments in Washington D.C., students design a brochure of the Monuments of Washington D.C.

Resources for Expression: See Assessment Strategies in the Accessing Inquiry pages for detailed ideas and tools.

Harris & Ewing. Library of Congress

"https://www.loc.gov/item/2016866965/"

UDL Teaching Strategies for the Classroom

- Search for "Teaching Strategies" and model "Lesson Plans" in the library of Teaching Resources.

- Paula Kluth's Universal Design Daily offers hundreds of concise ideas for implementing UDL–not social studies-specific.

- Understood.org offers a really useful worksheet, "Lesson Planning with Universal Design for Learning".