Companies

Few Americans in 1861 recognized the potential psychic costs of large-scale warfare. Diagnoses like shell shock, combat fatigue, and post-traumatic stress disorder did not appear until the twentieth-century. Nineteenth-century psychiatrists, largely the group of men who supervised a growing number of specialized asylums, used different words to describe causes of what they called “insanity.” In the Journal of Insanity, some of these men even argued that the war would give people purpose and common cause, so that war would be likely to reduce insanity.

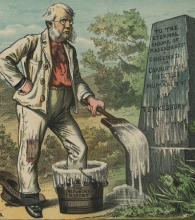

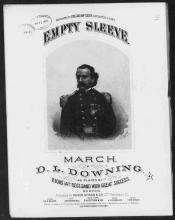

In the decades following the Civil War, the sight of armless or legless men on the streets of America was common. Though some amputations resulted from industrial accidents, most amputees were veterans who had lost limbs in battle. Because of the large size and slow speed of Civil War bullets, called Minié balls, soldiers unlucky enough to get hit felt their flesh shredded and bone shattered. Given the lack of antibiotics or even basic knowledge of germ theory, the only way a surgeon could save a life was often to remove a limb.

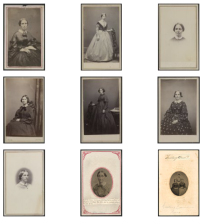

Many disabled Union veterans would not have survived the war without the efforts of the women of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC). Though Abraham Lincoln signed an order on June 9, 1861, creating the USSC, it was not a regular part of the rapidly expanding federal bureaucracy. The USSC was a non-governmental organization that gave the Union Army and government advice on modern medical practices, inspected military camps to promote hygiene, helped create an ambulance corps and hospital system, and raised money to pay for medical supplies.

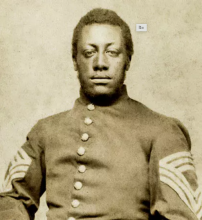

![[Private William Liming of Co. B, 21st U.S. Veteran Reserve Corps Infantry Regiment, and unidentified soldier in same uniform]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/2023-09/1862-1865%20Invalid%20Corps%20-%20Liming%20and%20another%20soldier.jpeg?itok=T39BJJQX)

The Invalid Corps, later called the Veteran Reserve Corps, was authorized by United States Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s General Orders No. 105 on April 28, 1863. It was a time during the Civil War when the Union had difficulty recruiting soldiers. Abraham Lincoln addressed that need in January 1, 1863 in the Emancipation Proclamation, which called for the enlistment of African American soldiers. Congress also passed the Conscription Act of March 3, 1863, the first mandatory military draft in U.S. history. The Invalid Corps was a third policy to expand the pool of available men.

During the Civil War, the United States Sanitary Commission sought information about European policies toward disabled veterans. The resulting report rejected the idea of housing large numbers of men in centralized national institutions, arguing instead that men should return to their local communities and be cared for by their families. What happened was very different from what the Sanitary Commission suggested. Thousands of aging and disabled veterans were housed in various regional branches of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

Tewksbury was the last place a disabled Civil War veteran would want to be. For many residents, it was a place to die. Anne Sullivan, its most famous resident who would later become “Teacher” to Helen Keller, saw her little brother, Jimmie, die of tuberculosis there.

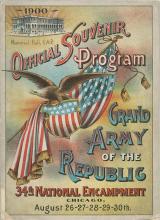

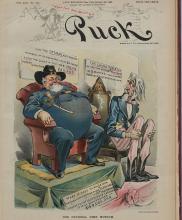

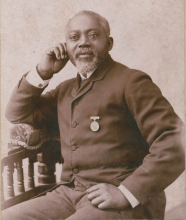

In the decades after the Civil War, there was no separate organization representing disabled Union veterans. Instead, like many other veterans, they joined the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). The GAR became very effective in pressure politics, especially in its promotion of veterans’ pensions in the late nineteenth century. It was, in effect, both a fraternal organization and a political advocacy group.

The first of the National Soldiers Homes was in Togus, Maine. In 1866, for $50,000 the federal government purchased a former resort at Togus Springs, four miles from Augusta, Maine. By 1870, the government had spent another $243,300 on improving the property. The number of disabled veterans living there rose rapidly during the years following Union victory. Within a year of its founding, 442 disabled veterans lived there. By 1878, 993 lived at Togus, and by 1904, at its peak, almost 2,800 men were cared for at the facility.

During the Civil War, the United States Sanitary Commission, local women’s associations, and many other groups helped disabled soldiers to transition back to civilian life. Yet such efforts were both temporary and inadequate. Many people called for the U.S. Government to intervene by creating a federally financed and administered asylum for disabled Union veterans.

Hundreds of thousands of disabled Union veterans sought financial assistance by applying to the Bureau of Pensions, a federal agency founded in 1832 but rapidly expanded after the Civil War. It eventually became a bureaucratic giant that managed the largest single item in the federal budget. The Bureau assessed disability claims and paid out benefits. In 1930, it was merged into the Veterans Administration.

People

“Having lost my right arm, which excludes me from most kinds of work, I have taken this method of gaining a living... I throw myself upon the generosity of the public.”

- The Empty Sleeve: Life and Hardships of Henry H. Meacham of the Union Army. By Himself.

“The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty.”

- Louisa May Alcott, Hospital Letters

“My Dear girl I hope again to see you. I must bid you farewell should I be killed. Remember if I die I die in a good cause. I wish we had a hundred thousand colored troops we would put an end to this war.”

- Lewis Henry Douglass, letter to Helen Amelia Loguen. July 20, 1863.

“The generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing.”

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Memorial Day speech, May 30, 1884.

“I had a strong inclination to prepare myself for the ministry; but when the country called for all persons, I could best serve my God by serving my country and my oppressed brothers. The sequel is short–I enlisted for the war.”

- Sergeant William H. Carney, letter in The Liberator from October, 1863.

Soldiers march as a group, in a clearing surrounded by canvas tents and some horses and cannons. In the corner, an artist, Deaf soldier John Donovan sits by a wagon as he draws the scene.

- Donovan, J. (1861). “Camp Brightwood, Colonel Henry S. Briggs. 10th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers. John Donovan, Deaf Mute, DEL Oct 17th 1861.” Library of Congress.

“My wound is still suppurating, and on account of a fracture of my skull, my head troubles me. My eye is gone—and, on the whole, I am very much used up. Time though, with the angellike tenderness with which I am cared for at home, will improve me sufficiently to recommence the practice of my profession. How strange has been my fortune! … The end is not yet.”

- Patrick Guiney, letter to Mrs. Shaw, June 2, 1864. (Samito, p. 247.)

“I have just got over that extreme soreness of the feet, which, I believe, has bothered all the nurses, except the real old stagers, whose muscles never surrender… The work is immensely hard, but I get used to it. If we could do it as citizens, instead of soldiers, it would be easy.”

- Hannah Stevenson, letter home, August 8, 1861

"I've done… three things… about healing over the years. One… is to… talk about what happened to me. The vast majority of Vietnam vets never talk about their experiences… I found great healing in being able to talk about it… "

- James Granger Munroe. Recorded 11/20/2002 for the Veterans History Project, Library of Congress.