Background Essay on the Steamboat Barnet

Introduction

The Connecticut River, now largely abandoned for economic purposes, once played a vital role in the commerce and industry of New England, and served as a major stimulus to the development of Springfield, Northampton, and other cities along the river.

In the nineteenth century, river improvements (canals and locks) and newly built turnpikes and bridges made overland trips faster and less arduous, but it was steam navigation that launched a fifty year period of rapid changes in transportation in the Connecticut River Valley.

In 1826, the Steamboat Barnet was the first steam-powered vessel to traverse the natural obstacle of rapids and falls in the Connecticut River and reach Bellows Falls, Vermont. Steam power meant that goods could be moved both down and up the river, a technological leap forward that contributed to the dramatic expansion of trade and commerce and the growth of cities in the Connecticut River Valley. Yet only thirteen years later, the railroad brought the era of the Connecticut River steamboat to a close.

Daily Canal Boat Line

Happy Fiftieth Birthday, America!

In 1826 Americans celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and the firm establishment of their republican government. The combination of expansionist energies that broadened the nation’s boundaries, liberties protected by the Bill of Rights, and the vigor of the youthful population boosted national morale and contributed to the growth of a dynamic commercial economy.

Americans recognized the need to build transportation systems that would support their growing economy, and during the 1820s, government and business took steps to develop the nation’s infrastructure. This included the construction of roads and canals. Transportation improvements promoted trade and communication and also generated excitement and optimism about the future.

The Connecticut River Lifeline

Throughout the colonial period, when few passable overland roads existed, the Connecticut River and its tributaries served as a trade route that helped to unify the river valley region geographically and economically.

The river served as a direct link between the small agricultural settlements of western Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire and the larger communities of Northampton, Springfield, and Hartford.

Farmers had tilled the fertile soil of the river valley from the seventeenth century, and in the early nineteenth century they continued to use the river to transport their produce to expanding markets. Loggers and fishermen shipped their goods downriver as well. In towns along the banks of the lower river, shipyards multiplied. The increasing commerce, including a vigorous trade in brandy and gin that led to the proliferation of highly profitable distilleries, served as a major stimulus to the growth of river towns and cities.

The Connecticut River was in constant use to transport goods and people locally, from town to town. It was also an important link in an extended trade route for shipping exports to distant markets as far away as the West Indies. The river was just as important throughout the long New England winter. During the winter months the frozen river was like a super-highway for wagons and sleds.

Like most of the United States in the early nineteenth century, the upper Connecticut River Valley was still largely agricultural, but a local industrial economy was growing rapidly. So was the population.

After the Revolution, from 1790 to 1820, Springfield almost tripled in size, increasing from approximately 1,600 to almost 4,000 inhabitants. In Northampton, the population nearly doubled. As the population and commerce grew, transport on the Connecticut River grew apace, and the Connecticut River became an increasingly important lifeline.

New Technologies

Before the Industrial Revolution people used flatboats—sturdy and stable flat-bottomed rectangular vessels designed to carry freight and passengers on inland waterways—but they were inefficient and slow. Sometimes flatboats were rigged with square sails, but when the wind was down, “polemen” propelled the boats along. Although shipment of goods by flatboat continued until well after the Revolution, the steady rise in commerce created a growing demand for improvements in water transport—especially for ways to overcome the obstacle of river rapids.

The rapids made the development of more efficient transportation challenging. In Enfield, Connecticut only flatboats carrying less than ten tons could be poled up the difficult rapids there. Workers had to transfer cargoes to oxcarts, drive the carts above the rapids, and reload. Just north of Springfield was another major rapid: the South Hadley Falls. At this location, the river dropped fifty-five feet over more than a two-and-a-half mile length.

Canals offered one solution to the problem of rapids. In 1792, twenty-five years before New York governor DeWitt Clinton proposed building the Erie Canal, business leaders formed the “Proprietors of the Locks and Canals on the Connecticut River.” Three years later they opened the canal to commercial traffic.

Most canals consisted of a series of locks that allowed a vessel to be raised or lowered to the height of the river. In South Hadley, they used a device called the “incline plane”. In a short time, many canals were built along the Connecticut River and trade along the river increased dramatically due to improved access to river ports in Western Massachusetts and beyond. Flatboats were soon transporting large quantities of iron, millstones, molasses, and rum up the river, while farm products, potash, lumber, and maple sugar traveled down the river.

At the same time, Americans were building new bridges and turnpikes. In 1805 construction teams completed the first bridge to span the Connecticut River and link West Springfield and Springfield. More than 3000 people gathered to dedicate it, a sign of public interest in this amazing feat. This and later bridges were technological marvels, spanning the wide expanse of river. A new bridge, built after the 1805 bridge washed away in a flood, was 1,342 feet long and thirty feet wide.

Steaming into History: The Steamboat Barnet

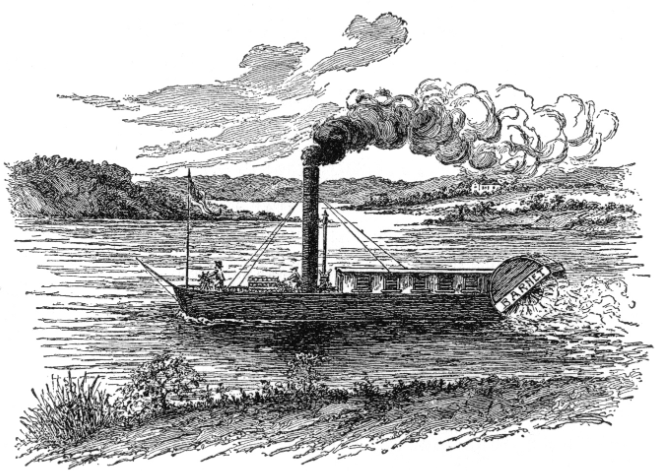

In 1822, New Haven merchants obtained a charter to build a series of canals from New Haven to Northampton. Springfield and Hartford entrepreneurs recognized that a successful New Haven canal was a serious commercial threat, so in 1824, they came up with a second solution to the problem of the rapids. They formed the Connecticut River Company and commissioned Brown and Bell of New York to build a steamboat that could navigate the Enfield rapids and travel north of Hartford. By November of 1826 the Barnet was ready to steam up the Connecticut River.

The steamboat left Hartford on November 17, but failed the first attempt to climb the Enfield rapids. Engineers strengthened the engine, and with the assistance of thirty men poling from flatboats lashed to each side, Barnet navigated the rapids. Letters written by eyewitnesses tell us that when the Barnet steamed into Springfield, townspeople thronged to the riverbank to see her, greeting her arrival with cannon, bells, and cheers. The Barnet’s maiden voyage proved that commercial steamboat operations were possible in the upper part of the river, and this meant expansion and progress. Barnet had steamed into Springfield with the future on her deck.

Meanwhile, in 1834 the New Haven merchants finally completed their canal. They opened for business in June of 1835, but their venture was a commercial flop. It lost over $140,000 in the first three years of operation.

Beyond the Barnet

In spite of the victory that Hartford and Springfield merchants won with the Barnet, the heyday of Connecticut River steamboat traffic was short. In 1830 several railroad companies obtained the first charters to develop lines out of Boston. By 1839, just thirteen short years after Barnet steamed up the Connecticut and over the falls at Enfield, the Western Railroad completed the first north-south railroad in the Connecticut River Valley and established lines connecting New Haven, Hartford, and Springfield.

By the mid-1840s, transportation and shipping through the rail network had trumped the steamboat entirely. In less than two decades, steam-powered river transportation and the system of locks and canals gave way to new technological developments completely unforeseen during the short life of the Barnet.

The Barnet had steamed into the past.

View an exciting primary source Inquiry Starter Set: "Full Speed Ahead: The Explosive History of 19th Century Steamboats” on the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources (TPS) Teachers Network.