Guest post by Nancy Spannaus

Origin of the American System

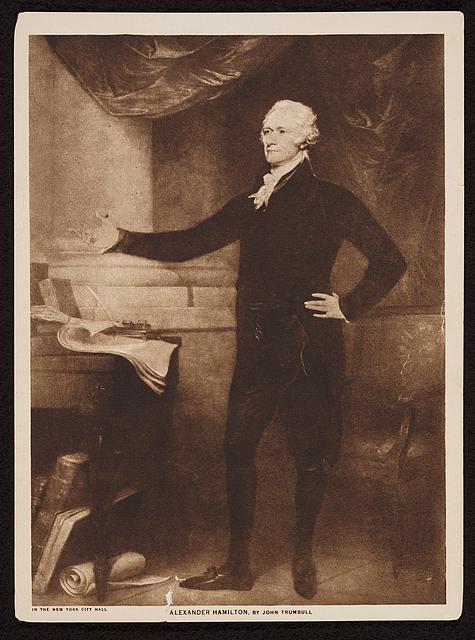

It is common practice to present the American System of Economics as the invention of Kentucky politician Henry Clay, who served as a leading spokesman for that policy in the Federal government from 1806 to his death in 1852. But in his advocacy for the key components of the American System–Federal protection for manufactures, national banking, and Federal support for infrastructure–Clay was actually continuing the work of First Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton.

Hamilton was even first to coin the term. In the concluding paragraph of Federalist Paper #11, he wrote: “Let Americans disdain to be the instruments of European greatness! Let the thirteen States, bound together in a strict and indissoluble Union, concur in erecting one great American system, superior to the control of all transatlantic force or influence, and able to dictate the terms of the connection between the old and the new world!”

As you can see, Hamilton’s key idea here is to liberate the newly established United States from its role as a dependent on the European economies. He is saying, in effect: What is the use of political independence, if we continue to be economically dependent on Europe?

He developed this idea further, in some depth, in his greatest state paper, the Report on Manufactures. This report was presented to Congress in December of 1791, in response to a Congressional mandate that he develop a plan for “promoting such as will tend to render the United States, independent on foreign nations, for military and other essential supplies.”

His overall objective was summarized as follows in that report:

“Not only the wealth; but the independence and security of a Country, appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of manufactures. Every nation, with a view to those great objects, ought to endeavour to possess within itself all the essentials of national supply. These comprise the means of Subsistence, habitation, clothing, and defence.”

The relevance of this concept continues to be shown today, in situations such as the lack of domestically produced vaccines during the COVID pandemic, and the dependence of many poor countries on food aid, because they have been told to concentrate their resources on producing certain products for export.

Hamilton’s Plan

Hamilton’s plan involved the following aspects: 1) the creation of a Federally backed source of credit, the First Bank of the United States; 2) a system of tariffs, bounties, and other financial incentives or penalties to support the “essential” sectors of the U.S. economy; and 3) Federal support for developing manufactures by helping fund physical infrastructure ( transportation, in particular), regulating quality standards, and creating an institution to promote “the prosecution and introduction of useful discoveries, inventions and improvements.”

While Hamilton was able to establish the Bank, implement most of his proposed tariffs, and initiate certain crucial infrastructure projects, such as the completion of a network of lighthouses to support safe shipping, his overall progress toward establishing a manufacturing base was limited. His first objective had to be to bring the nation out of bankruptcy by establishing public credit (making sure the government had a currency and could borrow), establish a secure revenue stream for the government, and stave off physical threats such as those on the nation’s borders.

He did, however, create a model industrial park in his Society for Useful Manufactures (SUM). That private corporation was established at the Passaic Falls in New Jersey, then the largest waterpower source under U.S. control; the complex served as the foundation of the city of Paterson. The plan was to set up a multi-industry center which would recruit skilled workers from Europe and launch a number of vital industries such as cotton goods, paper, shoes, and iron wire. The United States was still dependent upon England, in particular, for those products.

Contrary to what many say, the SUM went on after its initial troubles to become a major manufacturing center for the nation.

Hamilton’s plans were controversial in his day, and continue to be so today. Two of its foundations deserve further elaboration here.

The National Bank. The first has to do with the national banking system which he proposed and put into effect. Hamilton’s National Bank was conceived as a commercial bank, which means that it was intended not only to provide loans to the government when needed, but to provide credit to industry, agriculture, and commerce. Yet its seed capital was largely provided by Federal government bonds – ¾ of the payment for bank stock had to be comprised of those bonds. In effect, government debt was being turned into a source of credit for the economic activity the country required. [The Report on the National Bank was called the Second Report on Public Credit.]

The Bank’s opponents, who were generally opposed to the United States becoming a manufacturing nation, used the Bank’s reliance on government debt to attack Hamilton for wanting to keep the country in debt, or even increase the debt. Hamilton argued back that he opposed an “excessive” debt, but that this debt (the bonds) could be helpful to the nation by becoming an engine of productive investment. By this, he meant investment in industries, farms, and even infrastructure–whose creation would actually enrich the country and allow debts to be paid off at a reasonable rate.

The Bank of England also used government debt as a source of its capital, but there was a crucial difference. In Great Britain, the bank was a tool of the government, devised and used primarily to finance its wars. It did not invest in the private economy. Hamilton’s Bank, on the other hand, was intended to build up the U.S. economy by lending to manufacturers, localities, and farmers, as a necessary element of securing national prosperity and independence.

Direct Federal Support for Industry and Infrastructure. The second controversial foundation of Hamilton’s program was direct federal support for industry and infrastructure, ranging from tariffs, to subsidies, to building physical infrastructure.

Hamilton was an outspoken advocate for Federal investment on behalf of what he (and the U.S. Constitution) called the “general welfare” (which could also be called the public good). In his Opinion on the Constitutionality of his National Bank, he argued that federal powers, “especially those which concern the general administration of the affairs of a country, its finances, trade, defense & (etc.) ought to be construed liberally, in advancement of the public good.” His opponents argued that such “interference” in the economic affairs of the economy, or the states, was unconstitutional and a threat to liberty. As if Federal investment in creating a clean water supply, or improving commerce through dredging a river or building a canal, was a detriment to the population.

Interesting enough, British leading economist Adam Smith – and subsequent British political leaders – also opposed U.S. government support for development U.S. industry and infrastructure. Of course, the British government had acted to build up its industrial base. But the British were still not reconciled to the United States being fully economically independent, by building up its manufacturing base.

How Hamilton’s American System survived following the ascendancy of the anti-manufacturing party (Jefferson’s Republican Party) is a longer story, whose outlines can be found in my book Hamilton Versus Wall Street: The Core Principles of the American System of Economics.

Emerging America has three online exhibits on industrial development in the early American Republic:

- Steamboat Barnet discusses Henry Clay and the American System

- Forge of Innovation: The Springfield Armory and the Genesis of American Industry examines the successful implementation of interchangeable parts in the metalworking industry, made possible by U.S. Government sponsorship of the armory.

- Radical Equality: The Northampton Association of Education & Industry explores a communitarian alternative to slave-grown cotton founded by abolitionists.

Nancy Bradeen Spannaus is a public historian who has been studying American history, with an emphasis on its economic development in general, and Alexander Hamilton in particular, since the 1970s. In 1977 she co-authored a book of writings on the Political Economy of the American Revolution. After a career in journalism, in 2019 she self-published the book Hamilton Versus Wall Street: The Core Principles of the American System of Economics. In 2023 she self-published Defeating Slavery: Hamilton’s American System Showed the Way. She runs the blog https://americansystemnow.com, which contains more than 600 articles on the history and principles of the American System of Economics, and teaches a number of classes at Lifetime Learning Institutes.